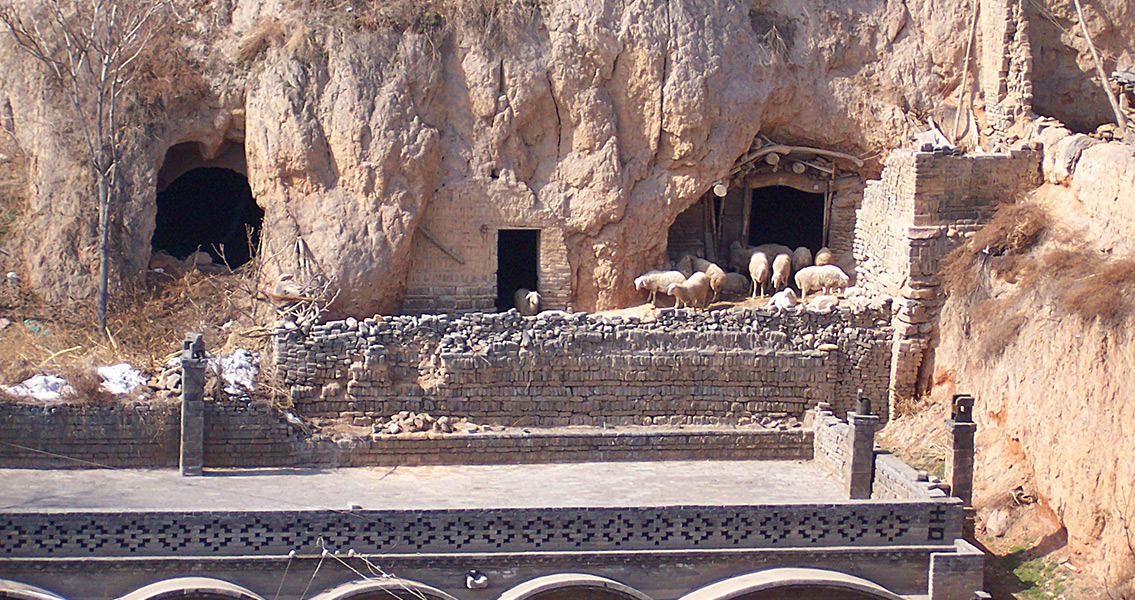

<![CDATA[On the 23rd January 1556 the deadliest earthquake in history took place in the Shaanxi Province, Northern China. Measuring around eight on the Richter scale, the medieval quake was far from being the most powerful in history, but striking in a densely populated area, it led to a horrific death toll. The earthquake is often referred to as the Jiajing Great earthquake, because it took place during the reign of Emperor Jiajing of the Ming Dynasty. According to contemporary sources, the epicentre was in the Wei River Valley, close to the cities of Huaxian, Huayin and Weinan. In Huaxian, every single building and home collapsed, and over half the population were killed. The extent of the damage was comparable in the other local cities. In total, an area covering roughly 500 miles was affected by the earthquake. The damage and after effects of the quake could be felt across an area including 97 counties, stretching over the provinces of Anhui, Gansu, Hebei, Henan, Hubei, Shaanxi, Shandong and Shanxi. In some of these counties up to 60% of the population were killed. Exact casualty figures for natural disasters are hard to determine, especially in those that happened so long ago, but estimates for the death toll in the Jiajing earthquake generally fall somewhere between 820,000 and 830,000 fatalities. Environmental consequences of the earthquake were also substantial. In some areas, crevices as deep as 20 metres opened in the earth. Mountains were leveled by the earthquake, and rivers had their paths altered, leading to major flooding. Massive landslides were triggered by the initial tremor, a major contributor to the death toll in mountainous areas. Fires started as a result of the earthquake would continue to burn for days after. The actual tremor on the 23rd January only lasted for a few seconds, but aftershocks could be felt every few weeks for the next six months, according to contemporary sources. A pivotal reason for the earthquake's devastating death toll was the nature of the buildings in pre-modern China. At the time, millions of people lived on the Loess Plateau. The Plateau covers much of Gansu, Shaanxi and Shanxi provinces, and is defined by the soft, fragile and erosion prone soil that covers much of the land there. The inhabitants of the area often lived in dwellings called Yaodongs, essentially artificial caves built into the side of cliffs. When landslides tore down the cliffs, the artificial caves built within them were buried with little warning. Historians know much more about this earthquake than might be expected for a disaster that happened so long ago. This is in large part due to the comprehensive annals kept by Chinese scholars from 1177 BCE onward. It is these annals that have revealed where the epicentre of the earthquake was, and provided detailed accounts of the damage caused. The annals describe the architectural devastation, as well providing explanations for the high rate of fatalities. Despite the devastation, the inhabitants of the area learnt from and responded to the disaster. Firstly, there is evidence of the catastrophe encouraging research into earthquakes - what they are and how they are triggered. Secondly, it led to a drastic change in lifestyles in the area, which can be observed through archaeological excavations. Following the tremor, rigid stone buildings and Yaodongs were abandoned due to their vulnerability to earthquakes. They were replaced with softer, more flexible buildings, made from earthquake resistant materials such as bamboo and wood.]]>

Deadliest Earthquake Hits China