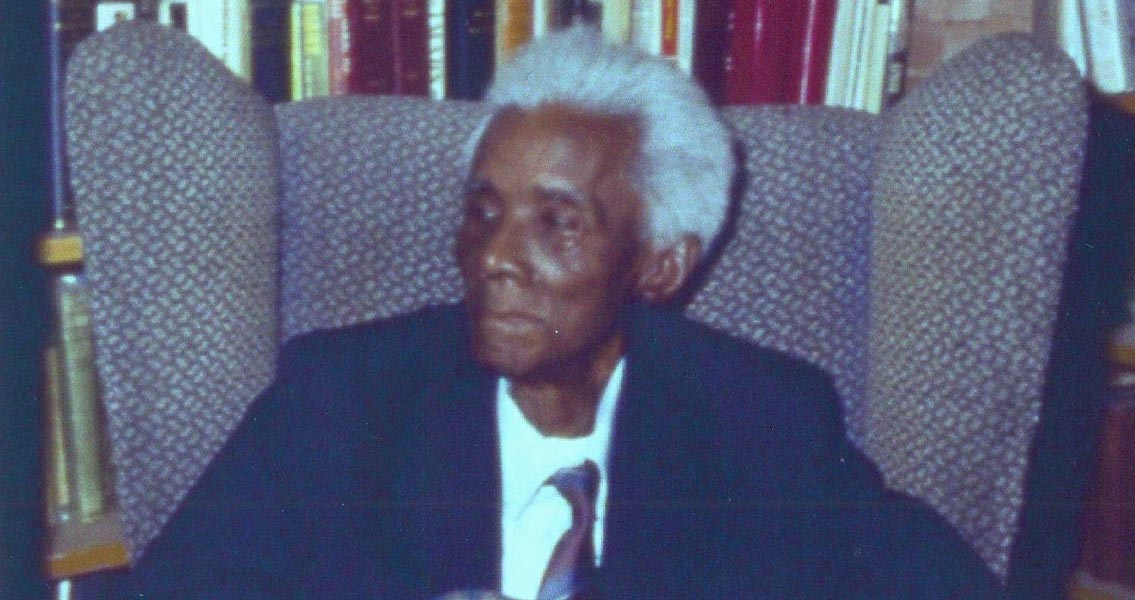

<![CDATA[C.L.R. James (1901-1989), author of The Black Jacobins (1938), a history of the Haitian Revolution, was a Pan African and independent socialist. Famous as a cricket journalist, literary man and historian, mentor of anti-colonial intellectuals such as Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Trinidad’s Eric Williams, his original political thought is still obscure. His advocacy of direct democracy and workers self-management are not irrelevant for understanding his speculative philosophy of history. How might James have evaluated the Ferguson, Missouri Rebellion in response to the police killing of Michael Brown? Or the mass mobilization in response to the police killing of Eric Garner in New York City where the police responsible were also not indicted? It is difficult to say exactly how James may have located these risings in Black History and Radical History. The gathering of oral histories from the participants in historical events or in the future the close reading of police reports which spied on and arrested some might tell us something the naked eyes of the world watching television and youtube videos cannot see at this time. Surely rebellions do not always have a revolutionary character, and the criminal element in the streets is not simply the imagination of conservatives. But human potential in rebellion has always been denounced as criminal and anarchy when it is far more than pejorative sentiment. Still, we have to ask these questions alert that it may be too soon to judge, but also that the evaluation of historical rebellions has always been a contentious enterprise among historians and even among radical thinkers. Further those that wield speculative and philosophical approaches to history have often been accused of seeking to insert missions and purposes into historical narratives that the facts could not confirm. Still we can speculate. Historians of rebellion have always speculated informed by their ideological predispositions, and so have politicians and media, in responding to events as they unfold, but also as they become memorialized. It is always difficult to speculate on what a historical figure might think of contemporary events. It can be more challenging if we wonder about the mind of a historian, as the field of history as a scholarly endeavor, its consensus standards and requirements, change over time. Though radical historians often disagree with the latter, most professional historians generally believe “history” is not the proper field of political consideration. Though it is remarkable that these cautious voices tend to approach relatively current history differently, where they accept world affairs can be made historical more quickly, if the evolution of nation-states, their statesmen and policies, are the subject recorded. President Obama was not the first historical figure to be placed in history immediately, just by showing up, without records found in archival research. The crimes of people above society, in any country or culture, do not impede them from becoming historical very quickly. Nevertheless, contemporary standard accounts of the profession of history and historiography (not just the facts but the debates and competing narratives among historians themselves as to how to craft history) cannot deny the forerunners of professional history today, are in fact speculative philosophers of history such as Vico, Michelet, and Spengler. What Type of Historian Was CLR James? CLR James, native of Trinidad, was a historian with a speculative philosophy of history. He brought these methods to his narrative of Haiti, The Black Jacobins (1938), and later Ghana, in his Nkrumah and the Ghana Revolution (1977). James was influenced by historians of the French Revolution, such as Jules Michelet, Peter Kropotkin, Georges Lefevbre, George Rude, Daniel Guerin, and Albert Soboul. His approach was also shaped by Leon Trotsky’s A History of the Russian Revolution, Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West, and the Edwardian radicals GK Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, both literary men who wrote polemical histories sympathetic to the social motion of commoners long before that, with more footnotes, was fashionable. James’s Notes on Dialectics explored the intersection of Hegel and Lenin as applied to the history of the international labor movement. But his original view of dialectics was just as much informed by how he understood the craft of writing history. For James, dialectic did not mean simply history moved by contradiction. Rather history was a series of ruptures with hierarchy and domination. At his best, he did not read history in a manner which placed as central the development of the nation-state. For James, the working classes, be their wages high or low, and the unemployed possessed a hidden depth, a latent understanding, and a creative genius. Ordinary people, not professional leaders of official society, were the chief actors of history. Humans faced institutionalized oppression, but also partial hindrances they placed in their own path as part of pursuing freedom. History did not move simply by materialist laws, but by romantic elemental drives where the dispossessed pushed from behind those who aspired to lead or rule. Statesmen and other heroic personalities were made by historical movements, but they could also be discarded by them. Revolutionary history was not just a revolt against aristocratic and conservative elements but liberal and progressive elites. The middle classes may have spoken for social change for a time, but wished to bring any rebellion to a brief end because they feared more those below society than those who governed previously and poorly. Those who rebelled did not know exactly what they wanted, and their best capacities could appear at one stage, disappear at another, and reappear in another epoch greatly enhanced to clean up the mess of a previous period. Insurgencies which toppled regimes in decay but did not complete the struggle for a new society might emerge again to complete historical missions. James could elevate all out of proportion to a direct democratic vision a heroic leader or charismatic personality. He could also suggest ordinary people had the capacity to directly govern society but that they will try everything short of that first, and will delegate authority to a leader, then rupture with one and then another. At the same time James was always striving to observe very closely, as a historian, the self-directed liberating activity of obscure leaders. Where there were not transparent transcripts or records, this required some imagination. Historical narratives for James were also a philosophy of becoming. James was critical of many historians who reject teleologies and imply another premise: historically oppressed peoples wished their lives to have no purpose at all. Part of cultivating the popular will for James as an activist was as a historian, recording their instinctive potential to solve problems they faced, and to elevate their contribution to freedom emerging within the shell of official society. If historical rebellions and social revolutions come to an end and cannot be the permanent subject of speculation, for regimes in response reconvert themselves, James contested that the continuous unfolding of popular revolt is the balance sheet of where the world is going, and the rate by which the democratic majority make their mark on a worldwide scale. James insisted in order to have democracy majority rule and opposition to the minority who rules above society was necessary. There was always a new leap in historical and political development to recognize and record. From the Haitian Revolution to African American Rebellion James’s The Black Jacobins is recognized with W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction and Herbert Aptheker’s American Negro Slave Revolts as pioneering the intersection of African American History and Radical History. The Haitian Revolution, as portrayed in The Black Jacobins, concisely speaking, is not simply a heroic tale about Toussaint L’Ouverture’s leadership. Though it is not insignificant that an African who had been a slave, and was seen by most purported rational observers of that epoch to be incapable of self-government, led the defeat of the French, British and Spanish armies, abolished slavery, and ushered in the first post-colonial regime. James also argued that Toussaint’s politics foreshadowed and faced all the problems of modern politics, from class struggle oriented social revolutions, to challenges of development for post-plantation peripheral economies. But there are two conflicting narratives threads in The Black Jacobins. It can be read as a guide for a vanguard party of future post-independence Black statesmen with warnings about obstacles they will face, and the mistakes they should not make in relation to the masses’ social motion. This makes popular revolt at a certain point something aspiring leaders must fear and manage. The story can also be read as an unveiling of the ordinary slave, whose names are unknown to history, who had been written off by official middle class opinion. Away from the plantation, where the slaves masked their true feelings around their masters, they practiced their own religions, arts, and had animated political debate. Out of the shadow of historical narratives that excluded their humanity or previously only feared them as subhuman, midwives poisoned those who policed them, and metal craftsmen and plantation workers observed closely how a global political economy functioned, as it was they who were the creative producers. James noted that the violence of slave rebellion was always modest and disciplined, however much it disturbed white authorities, compared to the memory of what mutilated African bodies experienced from sexual abuse and the lash. Yet some Haitian slaves, as freedmen, rebelled against Toussaint at the post-independence moment, reminding it was they who would decide what, when and how to produce. Yet Toussaint’s mind, restricted by feudal-capitalist notions of what type of economy was possible, led his Black army with the lash to attack the Black workers who wished to govern themselves. Somehow this did not undermine in most readers of The Black Jacobins a perception of an eternal heroism of Toussaint, as the first Black leader of a post-independence republic. But as James’s Toussaint himself proclaimed, from a Black perspective above society, law and order had to be maintained and anarchy, chaos and popular self-government could not be the basis of a new society. In James’s Beyond A Boundary, a semi-autobiographical meditation on the game of cricket, he reminds cricket is not just a sport, but it is the world of the working class and the colonized. James’s memories from childhood include Matthew Bondman, who like many other cricket players in Trinidad, were descendants of slaves. Bondman is among the barefoot men who curse and spit and disturb Black middle class propriety. Bondman is the embodiment of the vulgar, internalized stereotypes of white supremacy, and something to fear. But nobody, who is of social status, disputes that he can bat with grace and creativity. Progressives always seem to misinterpret Bondman, as James elsewhere in the book rejects the “welfare state of mind,” as a means of organizing cricket and politics. Bondman represents, for James, an unexamined truth greater than a culture of poverty. The unemployed and street force in a colonized nation, with all their creative capacity and self-organization, exposes that the politics of such a community is founded on lies. It is not simply that white racists cannot see it, but the Black middle classes do not see that ordinary Black people have the skills not just to get a job (if such were available) but to directly govern. If a society was designed differently that might become clear, but within the existing degraded community, the humanity of the marginal still astonishes despite prejudices claiming their inadequacies. James held Bondman in neither contempt nor pity. James wrote many essays on Black history and politics in his first American sojourn (1938-1953) which corresponds to the Age of the CIO labor movement. This activist-journalism included documentation of his work organizing a 1941 sharecropper’s strike in Southeast Missouri, a revolt of displaced Black farmers against white racist land owners, Jim Crow, and the policies of Franklin Roosevelt’s Agricultural Adjustment Act. These 1941 events were approximately three hours south of the Ferguson Rebellion of 2014. He chided both white and black historians about “key problems” in the study of Black History and that a new approach was required. African American history could not continue to compile a series of heroic personalities, known by their character, selflessness, and ambition. Historical facts, as facts, could do only so much. They had to be organized in a philosophy of history. James went further, they have to be cohered in a proper philosophy of history, for whether the scholar or writers is aware of it or not, they are always using a philosophy of history. James believed liberalism and the doctrine of parliamentary democracy, the framework of civil rights, perennially undermined the revolutionary implications of Black autonomy. James reminded it is not a unique American problem but a world problem. It is how the Puritan Revolution, French Revolution, or Russian Revolution is properly comprehended or not. Either oppressed people exist to protest as the wind behind a change in government above them, or they have the capacities to govern on their own authority. Can ordinary people reorganize society, using their immense powers, and not fall into the grip of a dictatorship? It is not a fatalistic question, but for James something worked out in historical narratives with a particular method. There was something wrong with African Americans being merely included in American History. There was something peculiar about more prosperous Blacks insisting on equal rights as citizens while never acknowledging the inherent exclusions of citizenship. In fact it was the Black slaves and marginal freedmen that took actions with the most revolutionary implications. There is a manner that Black History and Radical History can be told, argues James, which artificially enclosed the insurgent into coalitions with state power instead of allowing their self-directed liberating activity to expose its authoritarian nature. James’s methodology toward African American history can be summed up as “we have a false idea of the Negro” when we function as if ordinary Black people, with minimal formal education, cannot function consistently with the mainstream of revolutionary history. There is a tension between the striving for “equal rights” and a Black autonomy where everyday people can directly govern and design a new society. It is a speculative tension in how one approaches historical rebellions and crafts narratives. With these intellectual legacies how might have C.L.R. James approached the Ferguson Rebellion, even with the burning of property, and the subsequent rising in New York City? Do we not have to view these events as part of the long arc of the post-civil rights moment (not a moment beyond racism) where in many cities people of color hold the reins of power in government and workplaces? — The misunderstanding of the Ferguson Rebellion is not a problem of white racism alone. This outlook suggests that mainstream leaders in the African American community (church leaders, politicians and civil rights officialdom) have not also received the Ferguson insurgency as an embarrassment that fulfills racial stereotypes. In fact most have internalized and live by them. Certain middle class African Americans fear that Ferguson is a new development in politics. The young men, variously known for sagging their pants or not wearing belts, who have been decried for years as not having the discipline to be “successful” and take advantage of post-civil rights era opportunities, have exposed their critics’ bankruptcy. What has been this backward approach? In the African American past, middle class Blacks developed a politics of “racial uplift” at the turn of the twentieth century when lynchings in the US were at their height, and conventional racial ideas suggested Blacks were unclean, a lower life form, and unfit for self-reliance. In struggling to express an affirming Black identity, Black middle class ideas suggested their own personal and professional achievements in securing wealth and education proved that Blacks were not inferior. At times expressing valid pride, they were also expressing racial insecurity. Was the average white person in the Jim Crow era so distinguished in moral behavior that people of color paled in comparison? This was the main veil by which brutality hid in the past. Nevertheless aspiring Black elites promoted notions of service to ordinary Black people, which accepted their purported underdevelopment, and using phrases like “uplift the race” and “lifting as we climb” positioned themselves as agents of progress and culture. In fact they became managers of the dispossessed of the Black community. Marginal working class and unemployed Blacks, in particular perceived as embodying unpolished behavior, were their burden. Distinctions of social class, male domination, and elitism among women of color whom wished to minister to single mothers with children out of wedlock and chide free sexual lifestyles, accepted pejorative notions. Education was promoted heavy on manners and the importance of being clean and pressed to make a good impression. This was so in CLR James’s Caribbean and was present when he arrived in the United States. These Black elites desired to police those they held in contempt and pity and thus were limited in resisting white racism. Having the reputation for being “not like most blacks” they advanced their own careers benefiting from white patronage when available. There was always a dual sensibility among Black elites that white racism was both right and wrong to suggest ordinary Black people were not qualified for employment and full citizenship rights. The Black masses, to their mind, were not qualified and they prayed white racists could tell them apart in mixed company, that they would not be associated with their more troubled brethren. Yet suited Black people often found themselves equally booted by police brutality. Despite their arrogance, this reality sustained a certain unity, however reluctantly for those who poured scorn. Will it continue? When the Black Power era urban risings of 1964-1968 came, out of fear the American state began to reconvert itself to an affirmative action empire. Promoting the legacy of Dr. King’s dream (where previously they placed King under surveillance despite his advocacy of non-violent civil dis-obedience), African Americans who were college bound were now targeted by the government to make sure they got their piece of the economic pie. They would also be crucial to managing and distorting the meaning of Black disobedience. This is the background to many relatively comfortable African Americans lecturing the Ferguson rebels about the politics of respectability, responsible protesting, embracing the vote and courts as having the capacity to mediate justice, and not burning down “one’s own community.” It is also the foundation for challenging what cannot be explained. Corporate media in the streets of New York reminded that protests were mostly peaceful in contrast to the flames of Ferguson which they desired to discredit. Yet ordinarily civil liberties which promise freedom of assembly can lead in fact to five people who protest being arrested without a permit secured from police. Thousands of people can take over streets without permits and have the government and its police trail behind them in “peace” but also fear. One need not advocate this for this is a part of revolutionary history. For many years Bill Cosby and friends lectured young men about not embarrassing the race, only to reveal later their own pathologies and personal dirty dealings were compatible with economic aspirations after all. These annoying lecturers were especially pathological not because they were fond of making money, a widespread American pastime for those who can get it, but for condemning Blacks’ character equal to or more than the brutality perennially experienced. Further, the Black elite worked to use the vote to build the power of Black mayors and Black police chiefs beginning in 1972 in the aftermath of the uprisings of 1964-1968. The Black Power movement, as personified by the Black Panthers, emerged in between. This controversial cloud of dust and flames is the origin of President Obama’s premise that he represented “change we can believe in.” Other forms of change had been disavowed. Yet this has not been the empowerment those “without belts” can permanently relate. They prefer direct action, disobedience, and self-defense. There is this false notion that “Mike Brown cannot vote but you can” being peddled by those who will not take responsibility for Black run police terror in Atlanta, Detroit, and Washington and Black communities across the country. In fact Obama, Attorney General Holder, and Captain Johnson attempted to contain the rebels in Ferguson, whose lives have been degraded for years, by placing a veil of diversity over a white police force who had not yet entered the age of affirmative action. Yet equal opportunity to enter the rules of hierarchy will not solve the Ferguson rebels’ problems. The truth is we do not live in an Age of “a New Jim Crow”, but policing in most Black communities are administered by Black people. The Black church and Black civil rights officialdom confound the hesitant, but not the alert, for the Black Democrats. Majority Black cities and districts do not vote for white Republicans. Few marches are led exposing the complicity between Black “civil rights” and Black mayors and police chiefs – the responsible protesters are too respectful. University professors and media pundits generally don’t write about this peculiarity. But in Ferguson the rebels sustained an uprising against both white racism and Black officialdom. The heroic rebels’ actions overcame many burdens of family forms and limits of education some have known. If only their betters could do so well. The Ferguson rebels’ instinctive and latent understanding, their hidden depth, has proven more profound than the vote mob. How might CLR James, the historian, view all this? C.L.R. James, who was an elder mentor of Black Power and Black Studies movements, recognized that scholars of African American Studies must look for the obscure local leaders in any popular revolt. Rebellion will of course not be popular to anybody who is “somebody” in official society. But within the shell of the decaying society that cannot solve the problem of police brutality, some youth, many who have criminal records and minimal honors, and condemned to no viable economic possibilities, have projected a new political thread. The lies continue to be spread that formal education and the vote are the greatest tools of liberty. This was not so in the French or Haitian revolutions and it is not so in African American History. How did Black people organize themselves when the vote was denied them or not consolidated as yet? Do not even people with graduate degrees find scarce opportunities today? Our purported role models are being paid well to contain more than one rebellion. James observed the urban rebellions of 1964-1968, and judged that Black people, in contrast to decades before, expressed a new courage against the abuse of white police. This explosion in self-defense was something new. It was not embarrassing or fulfilling racial stereotypes. Internalized racism, whether by whites or blacks, projects a false idea of African Americans. But James in historical narratives illustrated other propositions. We must be able to witness that for many people of color “freedom” is a coveted position, patronage for a job, and for the formally educated their disposition toward independence, is really not much different than that of a colonial official who doesn’t believe the multitudes of their people can govern themselves. For those middle class elements who have contributed in the past to historical freedom movements we cannot hold them in permanent reverence for past service when historical conditions have moved on. The Ferguson Rebellion, including the burning of property, which happens in many historical rebellions, and every historical revolution (the former is not the same as the latter) appears to be a sustained revolt not just against white racist police but Black officialdom, including President Obama’s wishes. Even if the rebels do not know exactly what they want, and even if this does not foreshadow a new thorough-going social revolution anytime soon, this would seem to be a new historical and political development. History can be a contentious enterprise. Can it suggest that Ferguson is a new political development where ordinary Black people, who had been written off, not Black politicians and false civil rights activists, hold the reins of their own destiny? Hopefully with a reconsideration of history we can rethink who are embarrassing and backward. This is consistent with the intellectual legacies of the radical historian C.L.R. James. Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons user: Hill123 REFERENCES Alexander, Michelle. 2010. The New Jim Crow. New York: The New Press. Boggs, James. 2011. (1972) “Beyond Rebellion.” in Pages From A Black Radical’s Notebook: A James Boggs Reader. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. Gaines, Kevin. 1996. Uplifting the Race: Black Leadership, Politics, and Culture in the Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. Gilderhus, Mark T. 2007. History and Historians: A Historiographical Introduction. Sixth Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Hogsbjerg, Christian. 2014. C.L.R. James in Imperial Britain. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. James, CLR. 1983. (1963). Beyond A Boundary. London: Serpent’s Tail. James, CLR. 1971. “The Black Community and the Black Scholar.” Atlanta, GA: Institute for Black World, Audiotape of Public Lecture. Martin Glaberman Collection. Walter Reuther Archive, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan. Partial transcript In Vincent Harding Papers, MARBL Archives, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia James, CLR. 1963. (1938) The Black Jacobins. New York: Vintage. James, CLR. 1994. C.L.R. James and Revolutionary Marxism: Selected Writings, 1939-1949. Scott McLemee and Paul Le Blanc eds. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press. James, CLR. 1996. CLR James On The ‘Negro Question.’ Scott McLemee ed. Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press. James, CLR. 1992. (1947) “Dialectical Materialism and the Fate of Humanity.” Pp 153-181. In The C.L.R. James Reader. Anna Grimshaw ed. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1992. James, CLR. 2000. (1971) “How I Would Re-Write The Black Jacobins.” Pp 99-112. Small Axe. 8 (September) James, CLR 2000. (1971) “How I Wrote The Black Jacobins.” Pp 65-82. Small Axe 8 (September) James, CLR. 1977. Nkrumah and the Ghana Revolution. Westport, CT: Lawrence Hill & Co. James, CLR. 1971. (1948) Notes on Dialectics. Detroit: Friends of Facing Reality Moses, Wilson J. 2004. Creative Conflict in African American Thought. New York: Cambridge University Press. Quest, Matthew. 2013. “Every Cook Can Govern: Direct Democracy, Workers Self-Management, and the Creative Foundations of C.L.R. James’ Political Thought.” Pp 374-391. The CLR James Journal. 19:1&2 (Fall) Quest, Matthew. 2013. “From Mob Rule to Independent African American Labor Action: Reconsidering Anarchy and Civilization in Ida B Wells’s Anti-Lynching Campaign.” Introduction to Lynch Law in Georgia & Other Writings. By Ida B. Wells. Atlanta: On Our Own Authority Publishing.]]>

CLR James, the Ferguson Rebellion, and Radical History