<![CDATA[Last month, British historian David Starkey caused controversy on the BBC's Question Time program after mistakenly calling journalist Medhi Hasan 'Ahmed'. The response to Starkey's mistake saw him labelled a 'bigot' and a 'xenophobe'. Perhaps just as significant as Starkey's gaffe however, was the long speech that immediately preceded it. Discussing freedom of speech in relation to the Charlie Hebdo massacre, Starkey suggested that a lack of civil liberties had restricted the intellectual and cultural development of Islam. Of course, Starkey is entitled to his opinion and understanding of history. But this is not the first time he has made highly controversial remarks. Explaining the London Riots of 2011, he infamously claimed on the BBC's Newsnight programme that "The problem is that the whites have become black". Inevitably, these remarks caused a huge backlash against Starkey. Critics have often accused him of being nothing but a 'troll', an individual who deliberately insights anger in order to get a response. This might be true, but the controversies surrounding Starkey highlight that 'History', and the way people choose to remember it, are still deeply political, and capable of stimulating ferocious debate. History is a study of the past, but it has modern implications. A prime example, and someone Starkey alluded to in his comments on free speech, is David Irving. In 2006 Irving was sentenced to three years in prison in Austria for, "trivialising, grossly playing down and denying the Holocaust". He was released after thirteen months, but has since been banned from entering Austria, Germany, Canada and Italy. Holocaust denial, the act of downplaying or outright denying the holocaust, is illegal in a host of countries. Irving, who has subsequently denied his denial of the holocaust, still sticks to many of his revisionist claims about Nazism, the Second World War and Jewish history. Through selected use of evidence, he has tried to suggest that the history of Nazi Germany and its treatment of Jews has been distorted for ulterior motives. Irving is widely discredited as a historian, with few taking his work seriously. As an artefact however, he is deeply informative, embodying the continued connection between the past, the way it is remembered, and the present. Another example of a historian who revealed this continuing connection between the past and the present was the late Eric Hobsbawn. Hobsbawn was, and still is, a hugely respected historian. His trilogy of books on the origins of the modern world; The Age of Revolution (1962), The Age of Capital (1975) and The Age of Empire (1987), were groundbreaking in their fusion of the relationship between social sciences, history and economics, and are still read by history students to this day. Hobsbawm was also a member of the Communist Party in Britain, and unlike many of his contemporaries, remained a member even as the evils of Stalinist Russia and the Soviet Union started to be exposed. Hobsbawm had always deployed a Marxist form of analysis in the creation of his histories, and he stayed true to the economic and social ideals of Marxism up until his death, publishing a book in 2011 which defended left wing politics in the wake of the 2008-2010 global recession. At various points, Hobsbawm was accused of being an apologist for the crimes of the Soviet Union and Communist China. It is also apparent that his works of history were deeply affected by his own beliefs and context, equally, the reception they received was deeply affected by the contexts in which they were read. It is wrong to compare Starkey, Irving and Hobsbawm as historians. All three clearly have very different beliefs, and write for different audiences. More importantly of course, Irving has been widely discredited as an academic, even though it must be noted that there is still an audience for his self published works. What is clear however, is that the actions of all three show the implications in the present of the study of the past. There are of course other examples. A recent controversy between Latvia and Russia over a UNESCO exhibition on the Salaspils concentration camp, showed the real political ramifications of the way the past is depicted. Another example is the controversy surrounding Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan's public support of the argument that the Muslim faith was widespread in America before the arrival of Christopher Columbus. This was not just him voicing his view on history, the statement was made in support of a controversial proposal to rebuild a Mosque in Havanna. A clear example of a reading of history being deployed as a political tool. The controversies around Starkey prove a well established truth. History is permanently linked to the present. Historians, whether wittingly or unwittingly, can often find themselves commenting on now, as much as then. ]]>

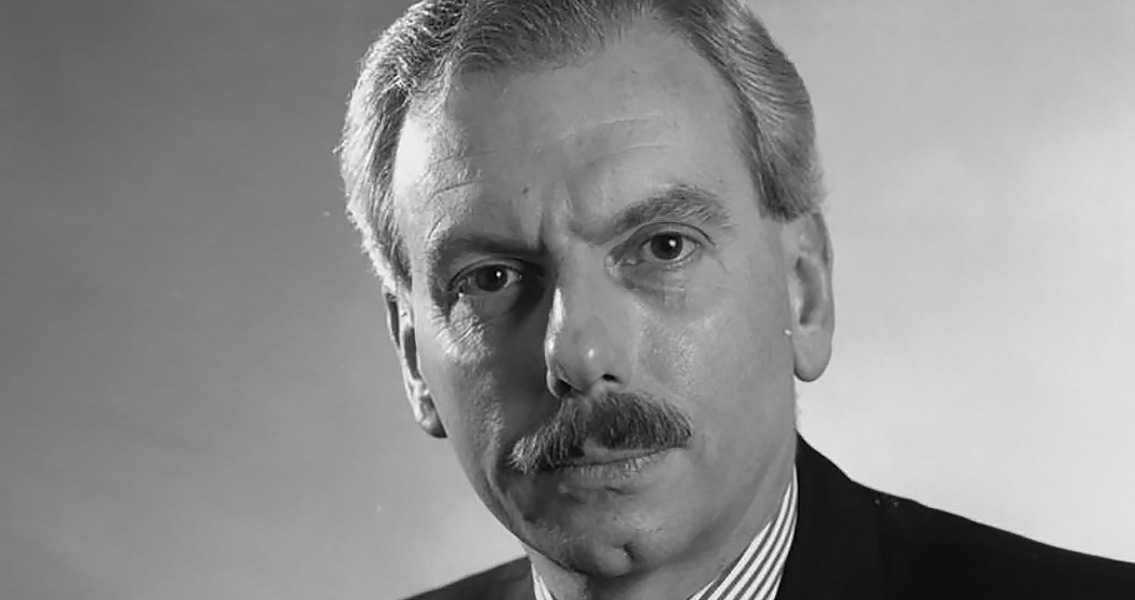

David Starkey: Historians and the Present