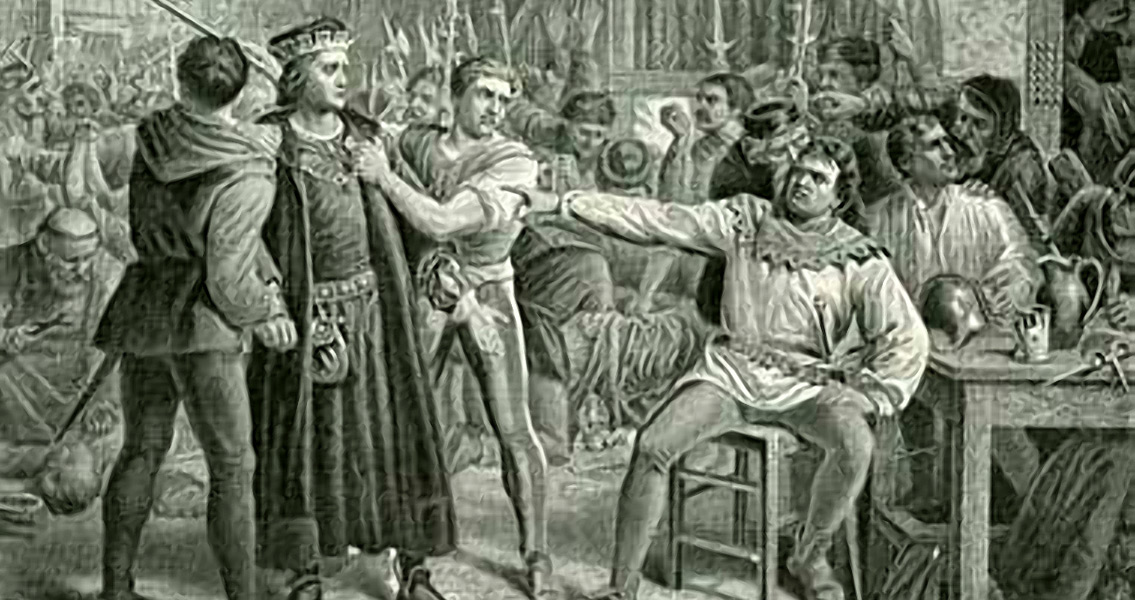

<![CDATA[On 8th May, 1450, a group of Kentish men led by Jack Cade began their revolt against King Henry VI. Ultimately marching to London, the rebellion proved a key marker of the breakdown in royal authority that resulted in the War of the Roses. Although led by property owners, the participants in the rebellion were mostly peasants from Kent, England, marking the event out as a key moment in the growing political consciousness of the non-aristocratic members of society. Unlike the Peasant Revolt of 1381, Cade's rebellion was not instigated by peasantry, but it pointed to the growing potential of the poorest in society to become a force that could be harnessed by those seeking to affect political change. The protesters objected to forced labour, corrupt courts, land seizures by the nobility and heavy taxation. Coming at the height of the seemingly endless Hundred Years War with France, the revolt was directly linked to the broader resentment at the royal management of the conflict. Henry's reign had seen a series of severe defeats, leading to the costly loss of territory on French soil. The Royal treasury had also been drained by the expensive war, leading to an increased tax burden across society. Such broad taxation in turn lead to greater opportunity for corruption, with tax officials taking advantage of an inefficient system to fill their own pockets. Cade and his followers defeated an army sent to Kent to suppress the revolt, before marching on London. They entered the city, and stormed the Tower of London, killing the Lord Treasurer: Sir James Fiennes, and the Archbishop of Canterbury. The two men's heads were cut off and placed on poles kissing each other. Initially, Cade's mob received support from Londoners who sympathised with their cause. However, the protesters' violence eventually started to alienate the city's population. Royal troops regrouped, and fought the rebels to a standstill. A truce was arranged, and Cade was given permission to submit his list of demands to royal officials. The officials promised that the demands would be met, and set about issuing a royal pardon to all those involved in the protest. Significantly, the King had not agreed to these concessions, a fact which would prove crucial later. Jack Cade himself was something of a mysterious figure, with even his name being far from certain. Of Irish descent, one account of his life suggests that in 1449 he lived in Sussex, but fled to France following an accusation that he had murdered a woman. In 1450 he returned to England and settled in Kent, posing as a physician named John Aylmer. At the start of the rebellion, he assumed the name John Mortimer, thus identifying himself with the family of Richard of York, a rival of Henry's who had been exiled to Ireland. Significantly, one of the demands on the petition submitted to the king was that Richard be recalled to England. Henry refused to allow Cade's audacity to go unpunished, and in June demanded that he be arrested. The Sheriff of Kent pursued Cade, and caught him on 12th July, 1250. Cade was injured in the confrontation, and died on the journey back to London. His corpse was hung, drawn and quartered, before his head was placed on a pole outside London Bridge. Many other leaders of the rebellion were also subsequently captured and killed. In the short term, the rebellion failed, with Henry refusing to implement any of the changes his officials had agreed to. Many of the participants in the revolt had been spared punishment, but the fate of the ring leaders sent a powerful message to any who may have been considering another rebellion. In the long term however, the Cade Rebellion highlighted the King's increasingly fragile hold on power in the run up to the War of the Roses.]]>

The Start of the Cade Rebellion