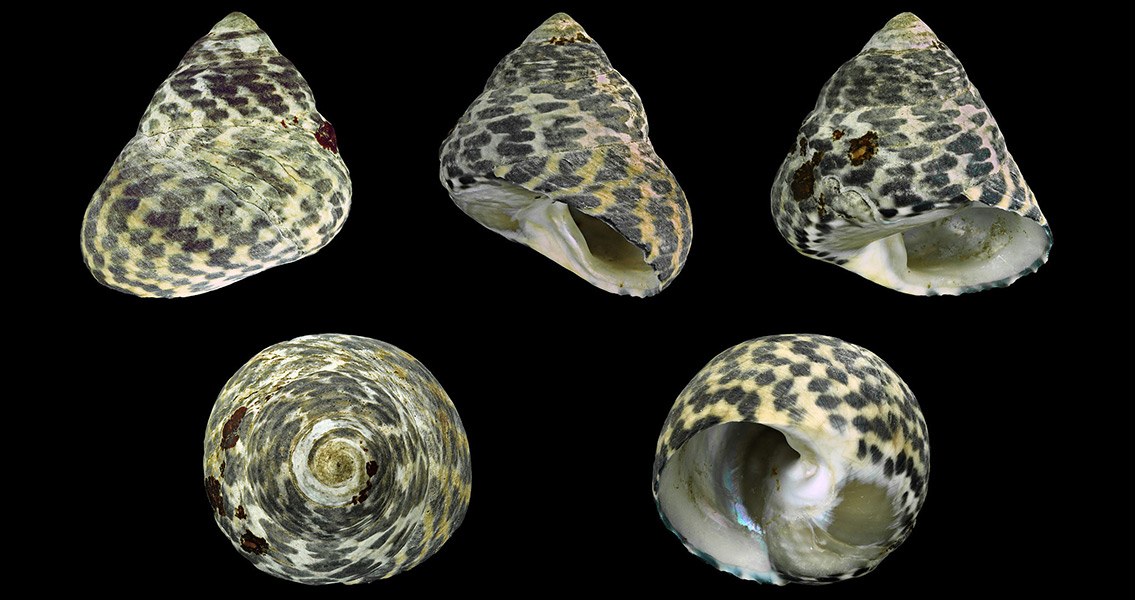

<![CDATA[Thousands of fossils of edible molluscs unearthed at an archaeological site in Lebanon have provided support for the hypothesis that modern humans entered Eurasia via the Levant. The international study that examined these, as well as human fossils from the site, was led by Marjolen Bosch from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. The authors concluded that the study result provides evidence for the Levant hypothesis, an important part of the debate regarding which route modern humans took once they left Africa. The team, comprising scholars from Germany, the UK, and the Netherlands, studied fossils of the Phorcus turbinatus, an edible mollusc that early humans ate, as evidenced by the broken upper shells of the animals. The fossils were uncovered at the Ksar ‘Akil site, where two sets of human remains from the Upper Paleolithic had been discovered previously. Combining the age of the mollusc fossils with that of the human remains, the researchers concluded that modern people lived in the Levant as early as 45,900 years ago, according to a press release by the Max Planck Institute. This is before the time modern humans settled in Europe, so the suggestion that they spread across the continent from the Near East was, according to the researchers, the only logical one. Another important suggestion from the study is the timing of this spread. This has also been subject of debate for a long time, mainly because there is scarce human fossil evidence from the early Upper Paleolithic period, Jean-Jacques Hublin, co-author of the study, said in the press release. Two human fossils, however, were found at the Ksar ‘Akil and have now been dated more accurately. One of the fossils, a man nicknamed Egbert by the team who discovered him, lived in the region around 43,000 years ago, during the early Upper Paleolithic. The other fossil, of a woman dubbed Ethelruda, was older, dated back to 45,900 years ago, a period that researchers call the initial Upper Paleolithic. Both fossils were associated by researchers with tools typical for the Upper Paleolithic and both were older than any Paleolithic human fossils from European archaeological sites. This, says co-author Johannes van der Plicht from the University of Groningen, suggests that modern human’s entry into Europe took place some time between 55,000 and 40,000 years ago. The conclusions of the scientists about the route of dispersal into Europe were supported by radiocarbon dating of the molluscs, an endeavour usually extremely difficult on shell remains. The team, however, used a new approach, as explained by Van der Plicht and another co-author, Marcello Mannino. They combined radiocarbon dating with biochemical datasets for more accurate results, including a technique examining the state of amino acids contained in the shells. What these revealed was a confirmation of the dating of the human fossils: modern humans lived in what is today Lebanon before they ventured northwest into Europe and spread across it, displacing the continent’s former masters, the Neanderthals. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: H. Zell]]>

Fossils Support Human’s Levant Route into Europe