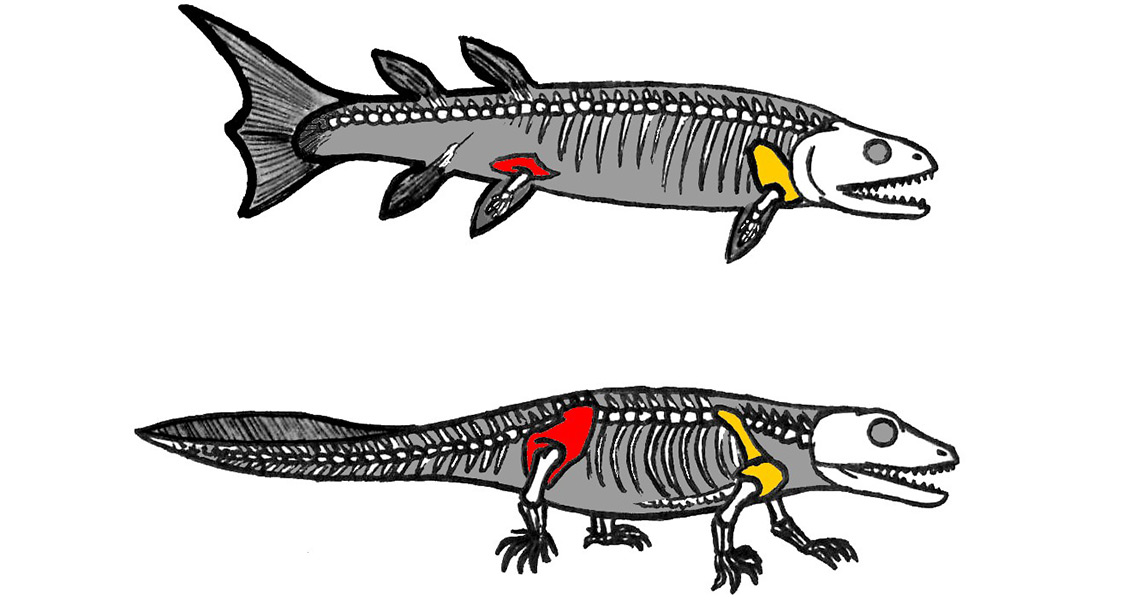

<![CDATA[The moment when the first four-limbed vertebrates - tetrapods - moved onto land was a key moment in evolution. Yet precisely how and when this momentous event occurred remains obscure due to a lack of fossil evidence. A recent study of a 333-million year old bone, however, is making scientists reconsider the evolution of when the first tetrapod left the seas and ventured onto land. Analysis of a fractured but partially healed radius (front leg bone) from a large, four-legged, primitive, salamander-like animal called Ossinodus pueri, found in Queensland, Australia, has pushed the date for the origin of terrestrial vertebrates back by two million years. Dr. Matthew Phillips, from Monash University, argues that the evolution of land-dwelling tetrapods was a significant evolutionary step. "Previously described partial skeletons of Ossinodus suggest this species could grow to more than 2m long and perhaps to around 50kg," Dr Phillips writes. "[The new fossil's] age raises the possibility that the first animals to emerge from the water to live on land were large tetrapods in Gondwana in the southern hemisphere, rather than smaller species in Europe. The evolution of land-dwelling tetrapods from fish is a pivotal phase in the history of vertebrates because it called for huge physical changes, such as weight bearing skeletons and dependence on air-breathing." The fractured bone analysed by Dr. Phillips revealed some interesting information. The nature of the fracture suggested to Dr. Phillips that the bone broke under a high-force impact, the fact that it had partially healed reveals that the Ossinodus survived the injury and lived afterwards for a time. "The break was most plausibly caused by a fall on land because such force would be difficult to achieve with the cushioning effect of water," Dr. Phillips notes. "Indeed, the fracture is somewhat reminiscent of people falling on an outstretched arm and the humerus crashing into and fracturing the radius." Other evidence from the skeleton confirmed that the tetrapod had spent a substantial amount of time on land. The internal bone structure was consistent with a remodelling during a lifetime subjected to the forces and strains generated by walking on land. "We also found evidence of blood vessels that enter the bone at low angles, potentially reducing stress concentrations in bones supporting body weight on land," Dr. Phillips explains. "The three findings taken together suggest that Ossinodus spent a significant part of its life on land. This is augmented by its exceptional degree of ossification, which is also consistent with weight bearing away from the buoyancy of water." This particular Ossinodus specimen is the oldest vertebrate yet found to have spent significant time on land. It is at least two million years older than the previous undoubtedly terrestrial specimens found in Scotland; these were also much smaller, measuring in at less than 40cm long. In his study, published in the journal PLoS ONE, Dr. Phillips argues that the findings have highlighted the value of combining studies on palaeontology, biomechanics and pathology to understand extinct organisms. Indeed, cross-disciplinary approaches enable experts to augment their understanding of a certain area by consulting other fields. For more information: www.journals.plosone.org Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user:Conty]]>

New Fossil Pushes Back When Animals Emerged Onto Land