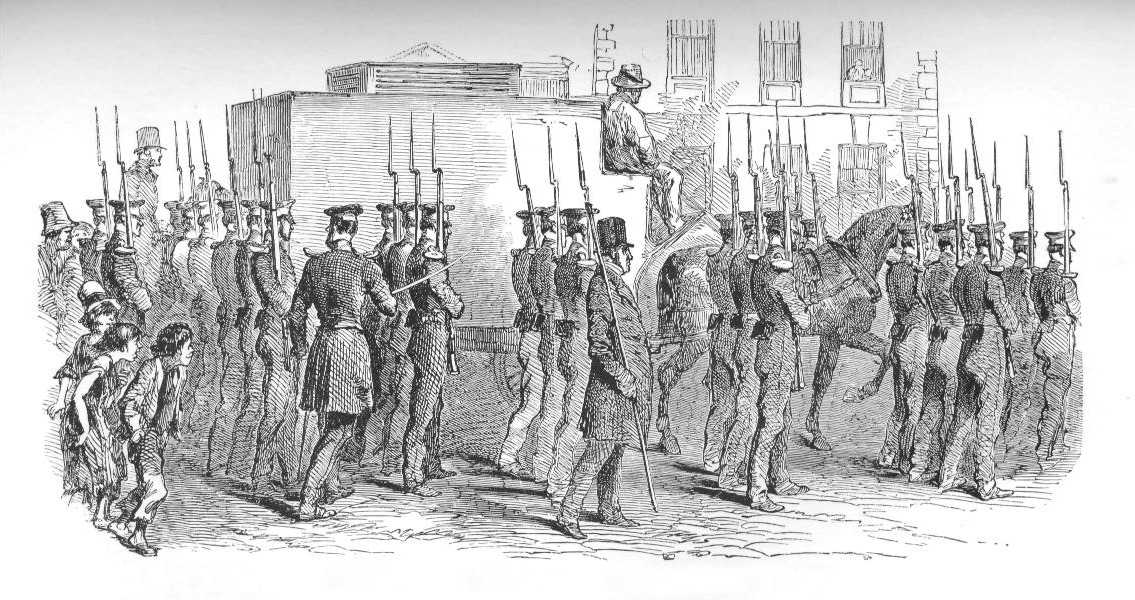

<![CDATA[On 29th July, 1848, the Young Irelander Rebellion was brought to a close with the arrest of William Smith O'Brien in South Tipperary. The nationalist uprising came during the Irish Potato Famine, a period of devastating food shortages which killed around a million people - an eighth of Ireland's population. Millions more emigrated from Ireland, heading abroad to the United States, Canada, and Australia. Initially triggered by a potato blight which lasted for three years in succession, the Famine robbed over a third of the Irish population of their regular source of sustenance. Inactivity on the part of the British government, which for the first few years of the famine did nothing in response, worsened the situation. Eventually the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, authorised £100,000 worth of corn to be imported to Ireland. The amount was a fraction compared to the quantity of food that had been lost in the famine, and starvation continued. Sentiment in Britain, by this point a country largely obsessed with free trade, was in favour of leaving the Irish to deal with the famine themselves. The dominance of absentee English landlords as the major property owners in the Irish countryside exacerbated the situation even further. Tenants who could not pay their rent were swiftly evicted from their homes. These same landlords, with purely a commercial interest in Ireland, also exported over a £1 million worth of corn and other food stuffs from Ireland during the famine, despite the country's desperate need for food, simply because the price was better in foreign markets. This sense that the British rule of Ireland had contributed to the severity of the Great Famine was a key motivation for the uprising of 1848. The wave of republican revolution sweeping Europe in 1848, particularly in France where Louis Philippe had been overthrown in an almost bloodless uprising, further encouraged the Young Irelander nationalists to believe that a repeal of British rule could be won. Events on the continent gave political reform groups greater belief that it was possible to achieve real change, each act of defiance inspiring another. William Smith O'Brien, along with John Mitchel, had founded the Irish Confederation in 1846 with the intention of freeing Ireland from British rule. By the summer of 1848 they had decided that the only way to achieve their aims was through direct action. The arrest and deportation of Mitchel early in 1848 under the Treason Felony Act signaled the levels the British government was willing to go to prevent dissent. On 22nd July, 1848, the government suspended the Haebas Corpus Act, meaning members of the Young Irelanders could be arrested without trial. The event forced O'Brien's hand, and preparations started for the rebellion with him calling the people of Tipperary to arms. The small band of nationalists met on 29th July and planned to declare an independent Irish republic. A brief battle, which saw the Young Irelanders fail in an attempt to capture a team of government police, effectively ended the revolt and the Irish nationalists were rounded up and arrested. O'Brien was later sentenced to death, although this was eventually reduced to deportation to Tasmania. A key factor behind the uprising's failure was that it lacked mass support from the Irish peasantry. The Great Famine may have helped inspire the decision to revolt, but it also meant that much of the Irish peasantry were far too occupied with merely ensuring their own survival to be willing to take part in a risky uprising. This combined with the Catholic clergy's refusal to back O'Brien ultimately left the uprising without the popular support base which had made the 1848 revolutions on the continent successful. ]]>

Young Irelander Rebellion