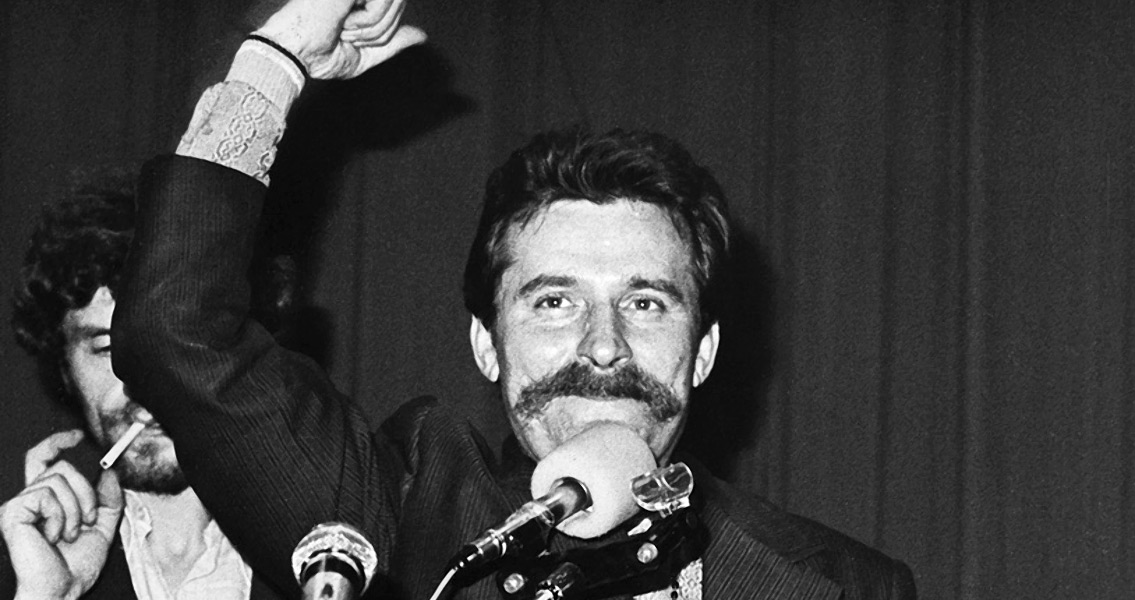

<![CDATA[On 31st August, 1980, the Communist government of Poland agreed to the demands of striking shipyard workers in the northern coastal city of Gdansk. The event was a key moment, not only in the history of Poland, but the Soviet Union as a whole. For the first time, an act of protest had won concessions from a communist government, rather than suffering repression. The dismissal of Anna Walentinowicz, a crane operator in the Lenin shipyard in Gdansk, was the immediate trigger for the strike. Activist workers, which Walentinowicz also was, had been planning a strike for improved conditions for some time. Walentinowicz's dismissal was the rallying call which pushed some 17,000 workers into action, demanding wage increases and her reinstatement. Worker activism had taken place in Soviet Poland before, and the 1980 protest had its origins in a protest which took place in Gdansk's shipyards a decade earlier. Forced into growing poverty by plunging living standards in Poland, workers at shipyards in Gdynia, Elblag and Szczecin, as well as those at the Lenin shipyards in Gdansk, took to the streets in protest. Forty four people were killed in the demonstrations after the army was called into restore order. Władysław Gomułka, the leader of the Polish Communist party, was eventually forced out of power in the wake of the uprising, but ultimately the authorities' response to the protest proved a reminder to citizens throughout the Soviet Union of the force with which dissent would be met. Nevertheless, the 1970 strikes helped lay the basis for what would happen in 1980. An economic crisis throughout the Soviet Union in 1980 saw the cost of living rise drastically, while wages remained static. Industrial workers struggled to make ends meet and afford even the bare necessities. Before the events in Gdansk strikes had taken place elsewhere in the country, although not on the same scale. In this context of distress and unrest a movement for change again started to gather momentum. Unlike in 1970, the strikers at the Lenin Shipyard in 1980 didn't confront the authorities directly, but instead locked themselves in their places of work. Despite attempts at censorship by the government, news of the unrest spread around the country, leading to strikes in other industrial cities. Fearing the strike could escalate further and become a full scale national revolt, the government sent a commission to Gdansk to negotiate with the strikers. On 31st August Lech Walesa, the leader of the strikers, and the Deputy Premier of Poland, Mieczyslaw Jagielski, signed an agreement which saw many of the workers' demands met. The aftermath of the strike saw the strikers, with Walesa as chairman, go on to create Solidarity (Solidarność in Polish), the first independent labour union in the Soviet Union. The national trade union quickly evolved into a massive social movement with over ten million members. By 1981 the government's tolerance of Solidarity came to an end, the movement was outlawed and its members forced underground. Nevertheless, it had gained recognition outside the Soviet Union, leading to the United States and its allies placing sanctions on Poland in response to the Polish government's repression of Solidarity. As a mark of the crucial role the movement had played in forging a Polish resistance to the Communist government, Walesa was elected Poland's first president following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989.]]>

Poland's Communist Government Agrees to Strikers' Demands