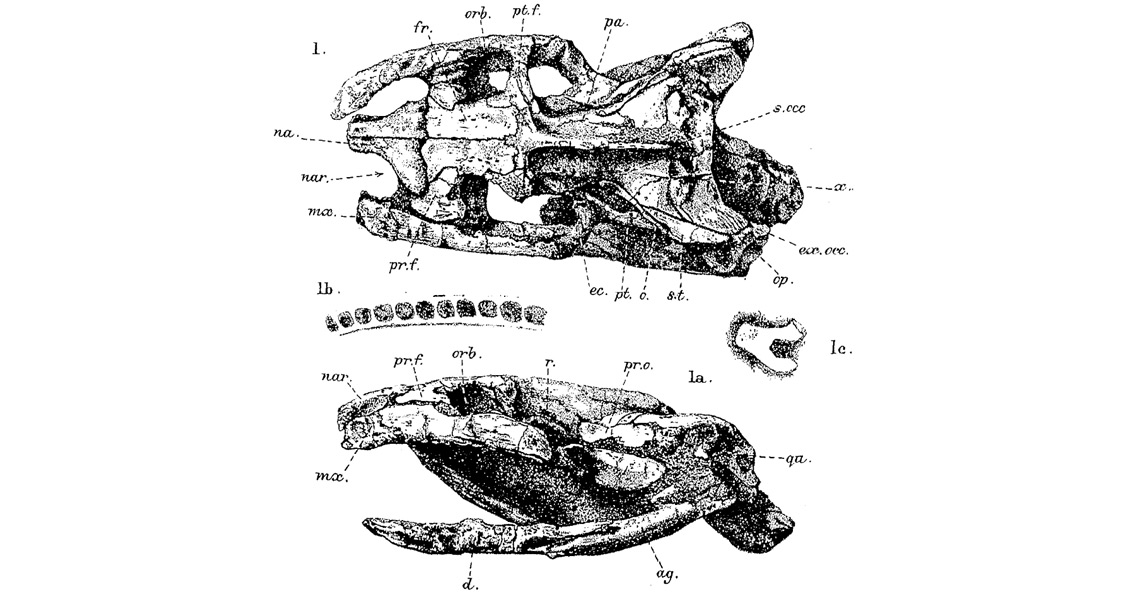

<![CDATA[Previous suggestions that snakes shed their legs in order to adapt to living in the world’s oceans may be turned on their head thanks to new findings by an international team of scientists. The research team, spearheaded by the University of Edinburgh’s Dr. Hongyu Yi and the American Museum of Natural History’s Dr. Mark Norell, used new computer-aided methods to take a closer look at the ancient remains of a 90 million year old snake ancestor known as Dinilysia patagonica. The scientists subjected a D.patagonica skull to CT scanning and then constructed three-dimensional virtual models in order to compare the ancient snake’s bony inner ear structures to those of modern snakes and lizards. The results point to snakes losing their legs around when they began to adapt to digging and burrowing in the ground, and not when they slipped into the sea. The lead scientists, in the research study published recently that described their findings, say that D.patagonica was likely to have been a burrower – and that modern crown snakes had ancestors that burrowed as well. The researchers used the shape of the inner ear to provide ectomorphic indicators for snake habits, as these details are often not preserved in fossilized remains. These specialized cavities in modern snakes control their ability to hear and their sense of balance, much in the way that the inner ear structures of D.patagonica are suggested to have done. The use of 3D modelling, based on the data gathered from the CT scans of the fossil, revealed distinctive structures that were analogous to those that burrowing animals have to provide them with additional abilities to avoid predators and hunt prey. These specialized adaptations are markedly absent from modern snakes that live above ground or spend time in the water. Such activities were common before modern snakes developed, but Dr. Norell and Dr. Yi claim that burrowing was an exclusive habit for evolutionary ancestors of crown snakes, as both D.pataognica and a theorized crown snake ancestor both possessed large inner ear chambers that have been associated with the ability to detect low-frequency sounds. This suggests that crown snakes had the ancestral ability to detect vibrations in substrate in order to detect predators and prey alike. The new findings may help paleontologists begin to fill in the gaps left in the narrative of snake evolution. The scientists said that the snake was easily more than 1.8 meters in length from snout to tail, crowning it as the largest burrowing snake ever. Additionally, the research findings have offered clues about an even older ancestor that may be the originator for all modern snakes alive today. For more information: www.advances.sciencemag.org ]]>

Snakes Lost Their Legs to Burrow Rather than Swim