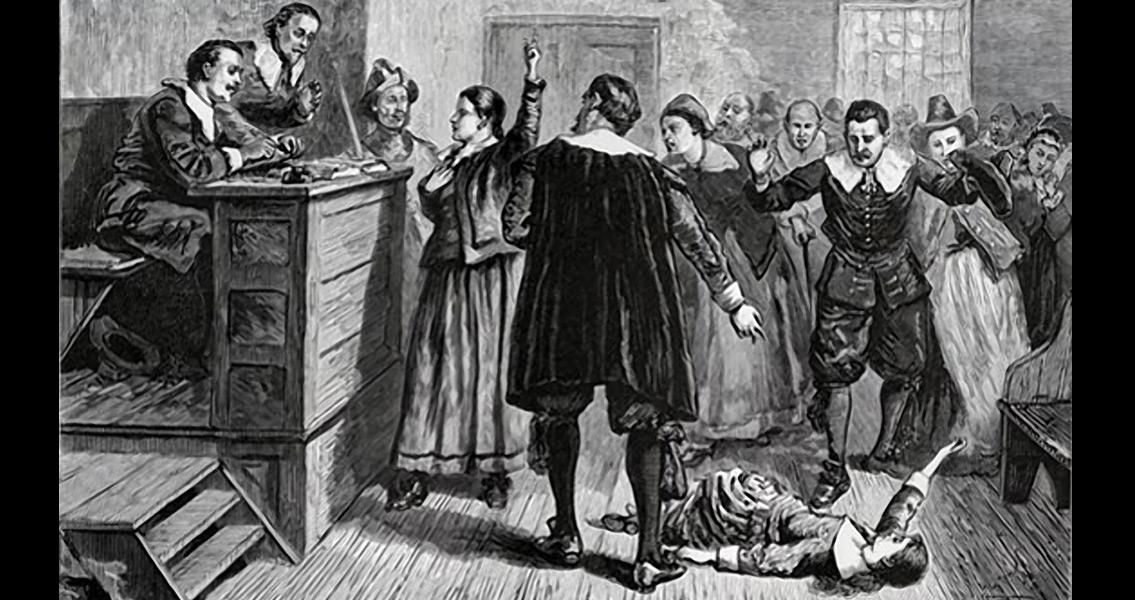

<![CDATA[The village of Salem, Massachusetts, declared a day of fasting and repentance on 14th January 1697, for the shocking witch trials which had taken place five years earlier. The acts of repentance extended to the whole of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Engaging in the fast showed that the people of Massachusetts were finally coming to terms with the brutal folly and hysteria that had engulfed the city, admitting that it had no biblical justification. The resolution which declared the day of fasting made the need to repent clear: "so all of God's people may offer up fervent supplications unto him, that all iniquity may be put away, which hath stirred God's holy jealousy against this land; that he would show us what we know not, and help us, wherein we have done amiss, to do so no more." The trials started with fervour and intensity in January of 1692. They continued until Spring 1693, although support for them had started to dwindle long before the trials officially ceased. Shortly after the day of repentance, the Massachusetts General Court declared that the Salem Witch Trials had been illegal, with leading justice Samuel Sewall apologising for his role in them. In 1711, the Massachusetts Bay Colony passed legislation officially absolving those who had been punished by the trials, and paid financial compensation to the heirs of those killed. Salem's repentance in 1697 surely suggests that the people there had a grasp of the irrationality and immorality of witch trials, so how had a deadly, paranoid fervour gripped the community so devastatingly just a few years earlier? The Salem Witch Trials began when two girls, the nine year old Elizabeth Parris and the eleven year old Abigail Williams; the niece and daughter respectively of Salem's minister, suffered from a series of severe fits, violent contortions and uncontrolled periods of screaming. The community's doctor, William Griggs, diagnosed bewitchment - kick starting the hunt for witches among the villagers. Arrest warrants were soon issued for Tituba; the Carribean slave of the Parris family, a homeless beggar named Sarah Good, and an elderly woman named Sarah Osborn. The three women had all been named by the children as the witches who had cursed them. What happened next is truly shocking. Brought before magistrates with the two children present in the court room and still suffering violent contortions, both Good and Osborn passionately denied the accusations against them. Tituba on the other hand, took a different approach. She confessed to the charge, perhaps hoping to save herself from the cruelest punishments, before claiming that there were other witches in the community employed by Satan himself to launch an attack on the village of Salem. Tituba's claim triggered mass hysteria. Some of those she accused would go on to accuse others, and fear of witchcraft gripped the community. Courts set up to handle the spiraling accusations accepted 'spectral evidence', that is, dreams and visions, as the basis of prosecutions. By the end of September 1692, nineteen men and women had been convicted of witchcraft and hanged. The event became a shocking example of the potential for fear, supersitition and paranoia to combine into a deadly hysteria. A whole community essentially turned on itself, people accusing others as a means to avoid being the accused. Unsurprisingly, the Salem Witch Trials have been used as an analogy to talk about anything from McCarthy's crusade against communism in the Cold War USA to the deadly hunt for scapegoats in Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany.]]>

Salem Repents For Witch-Trials