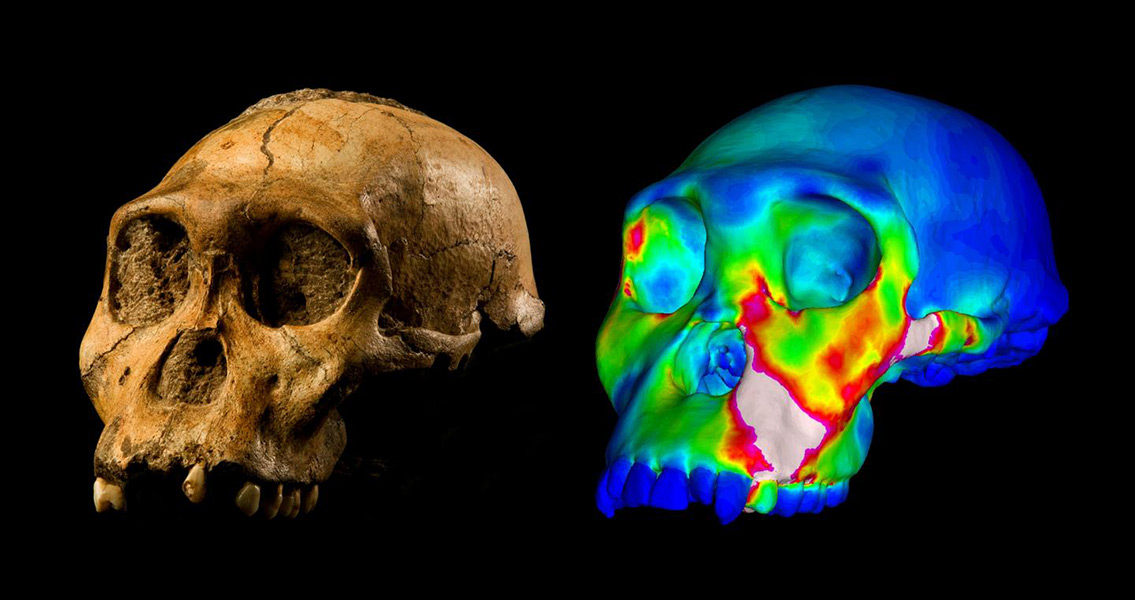

<![CDATA[New research has provided insight into the complicated ways dietary changes could have shaped the evolution of human ancestors. The focus of the study, published in the journal Nature Communications, was Australopithecus sediba; a species first discovered at the archaeological site of Malapa in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site, South Africa, in 2008. A.sediba‘s phylogenetic relationships have been a source of debate since its initial discovery. Some have hypothesized that A.sediba was close to the genetic ancestry of the Homo genus, while others have suggested that it was in fact a phylogenetic relative of A.africanus. Although not answering the question of whether A.sebiba is a close evolutionary relative of the Homo genus, the new study does provide insights into the evolution of early human species. A 2012 study argued that A.sediba lived off a woodland diet, including hard foods mixed in with tree bark, fruit, leaves and other plant products. This conclusion was based on dental microwear data, which seemed to show tooth damage indicative of a diet of hard to chew foods. The authors of the new paper have used mechanical tests on a model of A.sediba’s skull to show that in fact the creature did not have the requisite tooth and jaw structure to survive on a diet of hard foods. Indeed, the study suggests that if A.sediba had bitten down as hard as possible with its molar teeth, it would have dislocated its jaw. To test the biomechancial properties of the A.sediba skull model, the team used techniques similar to those deployed by engineers to test whether airplanes, vehicles, and mechanical devices will break during use. Significantly, these new findings seem to distinguish A.sediba from other members of the Australopithecus genus. “Most australopiths had amazing adaptations in their jaws, teeth and faces that allowed them to process foods that were difficult to chew or crack open. Among other things, they were able to efficiently bite down on foods with very high forces,” said Professor David Strait, team leader and anthropologist from Washington University in St. Louis, US, in a press release. It is widely believed that humans are descended from an australopith ancestor. Since its discovery, A.sediba has been considered a possible candidate for that ancestor, or at least a close relative to it. The limitation in biting force discovered by the team is something A.sediba shares with modern humans. “Humans also have this limitation on biting forcefully and we suspect that early Homo had it as well, yet the other australopiths that we have examined are not nearly as limited in this regard,” said co-author Dr. Justin Ledogar, from the University of New England in Australia, in the press release. “This means that whereas some australopith populations were evolving adaptations to maximize their ability to bite powerfully, others (including A. sediba) were evolving in the opposite direction.” Ultimately, the new study shows the impact of diet and ecology on the development of the Homo genus’ ancestors. The difference in jaw strength among australopiths revealed by the study suggests ecological factors disrupted their eating patterns and behaviours, thus causing different evolutionary adaptations. As the study explains, “Thus, even if A.sediba and Homo were descended from different gracile australopith ancestors, it is evident that one must understand the dietary selective pressures that influenced the ancestors that preceded the earliest members of Homo if one is to understand the origin of the genus.” For more information: www.nature.com Image courtesy of Brett Eloff provided courtesy of Lee Berger and the University of the Witwatersrand.]]>

A.Sediba Likely Ate Similar Food to Homo Sapiens