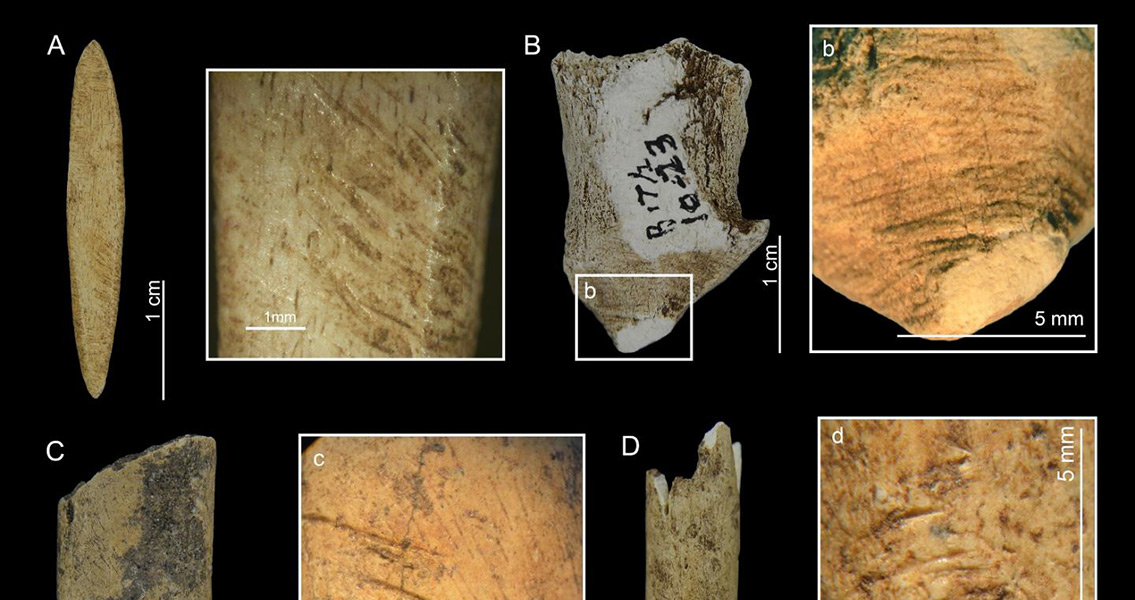

<![CDATA[A dwarf deer species native to Panama’s Pearl Islands was hunted to extinction around 6,000 years ago, according to a recently released research study. Prior to the end of the last Ice Age, sea levels were much lower than they are today. Yet 8,500 years in the past, these levels rose as the polar ice caps receded, isolating the archipelago off the Pacific coast of modern-day Panama. Such island regions are often found to provide excellent insights into evolution, in much the same way that the Galapagos Islands were so instrumental in Charles Darwin’s studies of how animal species diverged and adapted to their new environments, and the Pearl Islands are no different; recent archaeological discoveries have found a tiny deer species that existed on the island of Pedro González. Pedro González was settled around 6,200 years in the past. Islanders inhabited the 14-hectare island for up to 800 years, cultivating roots and maize, fishing the waters offshore, gathering coastal shellfish and palm fruits, and also hunting the local wildlife. Besides snakes, iguanas, agoutis and opossums, the locals also routinely hunted the tiny deer species – and were likely the direct cause of the dwarf deer’s extinction. In a press release from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama, archaeologist Richard Cooke described his first intimations of the one-time existence of the diminutive ungulate. The STRI researcher and the recent study’s co-author recalled how he had been cleaning animal bones from a 2008 excavation when he came across a calcaneum, a deer ankle bone, which was too small to be from anything other than a dwarfed species – one that had diminished in size thanks to its long isolation on the island. Study of evolutionary divergence in isolated populations tells us that limited food resources often result in size reduction in order to alleviate the pressures of competition within species stranded in island locations. This miniaturization doubtlessly occurred in the time between the sea levels rising and causing the local dear population’s isolation and the discovery of the island by pre-Colombian settlers around 2,000 years later. Studies of the deer remains indicate that the dwarf species was probably around 22 pounds or so when fully grown – a figure that the researchers point out is roughly the weight of a small dog species like a beagle. Mike Buckley, a biochemist from Manchester University who was involved in the study, said that collagen fingerprint analyses of the island deer revealed that they were unrelated to Panama’s native corzo, or red brocket deer, a similarly small-sized modern deer species. Instead, the deer populations of the island included mostly white-tailed deer, though there were also some South American gray brocket deer remains found as well. While DNA analysis will be able to provide a more clear-cut identification of the clade the deer belong to, Buckley says that the ancient deer are almost certainly related to a larger species still living around 5 miles to the south on the Pearl Archipelago’s San José Island. Why these deer survived to the modern day while their close cousins succumbed to extinction is yet to be determined. The journal article, which is currently only available in Spanish, can be found online here Image courtesy of STRI]]>

Island Deer of Panama Hunted to Extinction Long Ago