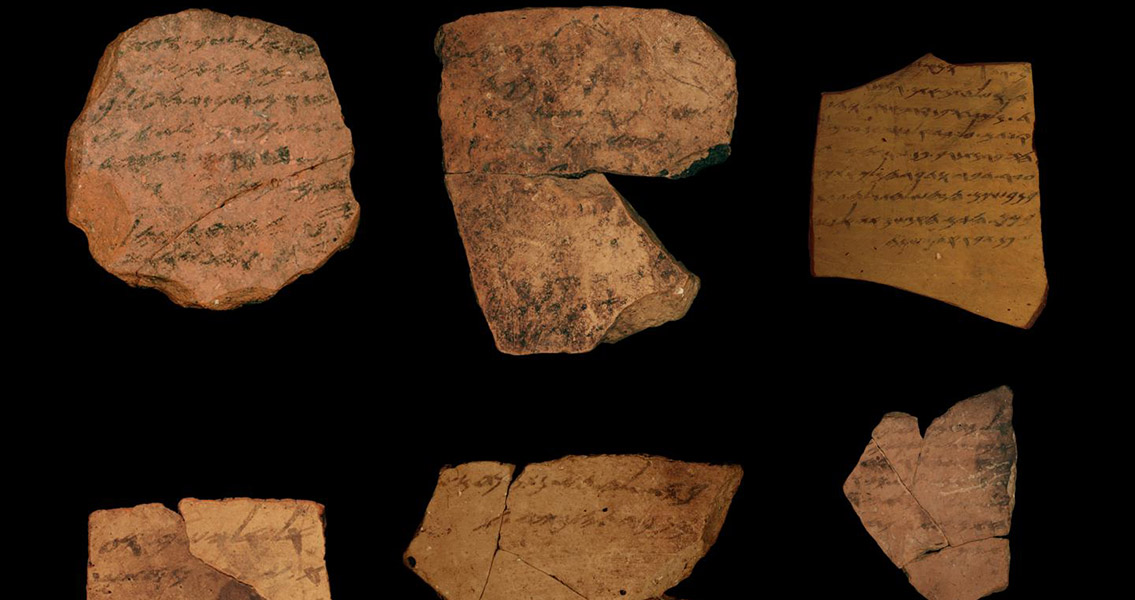

<![CDATA[A research study from Tel Aviv University has used handwriting analysis to shed new light on the mysteries surrounding just when Old Testament texts were written. The Torah, the Hebrew bible that is also shared by Christians, is thought to have been penned in large part around the seventh century BCE. The precise date is still unknown however, and other scholars have long wondered whether some of the texts that make up the Old Testament date to prior to the Babylonian Exile in 586 BCE, when the Kingdom of Judah ceased to be independent. The key in making this determination, according to the researchers involved in the study, is the level of literacy that existed in Judah prior to its fall. A high number of literate Judahites would have been necessary to provide the framework of several Old Testament texts, according to research team co-leader Professor Israel Finkelstein, from Tel Aviv University’s Archaeology Department. In order to understand just how literate the ancient Judahites were, the research team subjected 16 ancient inscriptions to computer image processing. The inscriptions, which were found during excavations at the ancient fort of Arad; east of the central city of Be’er Sheva, are thought to have been penned by a minimum of six different individuals. According to a Tel Aviv University press release, Barak Sober from the university’s Department of Applied Mathematics aided in designing a complex computer algorithm in order to tell these different authors apart. A statistical mechanism was used to make assessments, and the team was able to provide a high level of certainty that the texts were indeed written by multiple authors. The contents of the inscriptions themselves are relatively mundane, as they are the remnants of military correspondence from the troops stationed at the ancient fort. However, the various missives, which deal with logistical commands such as food expense registration and troop movements, were written in such a way as to support the hypothesis that literacy was widespread – from commanders down the chain of command to lowly quartermaster officers. As the soldiers stationed at a remote outpost like Arad were literate enough to write their own messages, the researchers took this as evidence of an educational infrastructure that would have spread literacy beyond a cloistered ruling elite. Prof. Finkelstein remarked that, by extrapolating from Arad and combining data gathered from other ancient administrative centers and military forts, estimations can be made that during the last phase of the First Temple period, prior to the Babylonian Exile, a large number of Judahites had the ability to read and write – at least several hundred out of the 100,000-strong population. The next period that provides evidence of widespread literacy is not until the second century BCE, the researcher added, making it less likely that Biblical literary pursuits of any substance in Jerusalem occurred between 586 BCE and 200 BCE. The research study, which was recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, can be found here Image courtesy of Michael Cordonsky (photographer), Tel Aviv University and the Israel Antiquities Authority]]>

Handwriting Analysis Sheds Light on Biblical Timeline