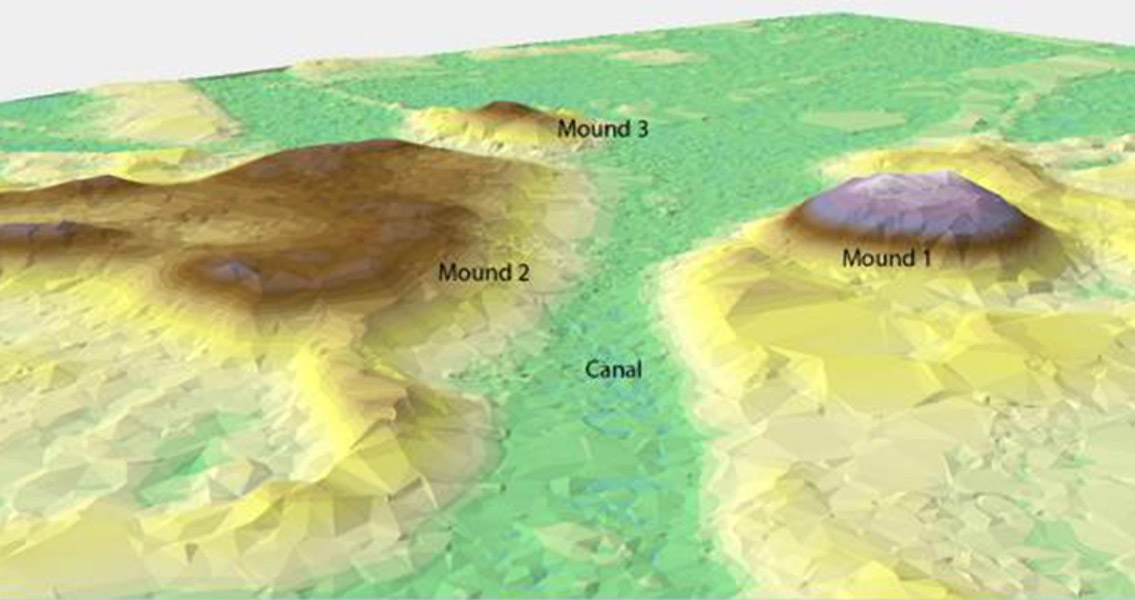

<![CDATA[A new study has provided fresh insights into Mound Key, an artificial island constructed by the Calusa people. The interdisciplinary project, led by University of Georgia anthropologist Victor Thompson, has looked at how the composition of the island changed over the centuries, particularly in relation to environmental and social shifts. The team's results were published this week in the open access journal, PLOS ONE. A pre-Hispanic polity with a population as high as 50,000 at its peak, the Calusa Kingdom controlled much of what is now South Florida prior to the arrival of Christopher Columbus. Revealing the sophistication of pre-Columbian societies in the Americas, the Calusa were building their own water bound settlements centuries before such practices were adopted in the form of artificial islands in China and Dubai. These islands were created from shells piled into massive heaps, sometimes as high as nine metres above sea level. One of the largest and most well known of these sea borne settlements is Mound Key, situated in what is now Estero Bay, close to Fort Myers Beach in Florida. When Columbus reached the New World in the fifteenth century, Mound Key was serving as the capital of the Calusa kingdom. Thompson’s team used a combination of systematic coring of the shell deposits, excavations, and intensive radiocarbon dating to study the development of the anthropogenic island. Their findings have afforded unprecedented insight into the island’s creation, inhabitation and development. “This study shows peoples’ adaptation to the coastal waters of Florida, that they were able to do it in such a way that supported a large population,” said Thompson, in an interview with the University of Georgia. “The Calusa were an incredibly complex group of fisher-gatherer-hunters who had an ability to engineer landscapes. Basically, they were terraforming.” Heaps of shells, bones and other discarded objects, known as midden, were used in the construction of the island. One of the most remarkable discoveries by Thomspon’s team is that this midden wasn’t in fact uniform from top to bottom. One would assume that the midden would be piled up with the oldest material buried at the base, and the newest closest to the top, but radiocarbon dating proved this was not the case. In many instances older shells and charcoal fragments were found above younger ones. Thompson and his team believe this shows that the midden was being reworked and reshaped, moved around to create new landforms for a variety of different purposes. “You’re talking hundreds of millions of shells. … Once they’ve amassed a significant amount of deposits, then they rework them. They reshape them.” The authors hypothesise in the study that this unexpected distribution of the midden can be explained by the island’s abandonment and then reoccupation. During periods of cooler temperatures, when fish were scarce, it seems the Calusa abandoned the island, only returning when the climate warmed and fishing became productive once again. This second period of occupation saw a host of large scale labour projects initiated, giving the island the shape it has today. A major conclusion from Thompson et al.’s study is that Calusa culture was far more complicated than traditionally believed, and in need of further study and reassessment. In particular, the team have gained insight into just how creative this society which the Spanish characterised as ‘war like’ really was. The Calusa had sophisticated methods to deal with environmental changes and fishing surpluses, to sustain their civilisation. “Our research there over more than 25 years has provided an understanding of how the Calusa responded to environmental changes such as sea-level rises.” Thompson said in the interview. “They lived on top of high midden-mounds, engineered canals and water storage facilities, and traded widely while developing a complex and artistic society. It takes a team of scientists with different skills working together to discover how all this worked.” The team have only scratched the surface of this fascinating culture, and are returning to the site in May to undertake even more research at Mound Key. “There’s a whole story that goes along with this site. It’s a laboratory that allows us to explore many different things, some of which are important to the present and the future and some of which are important to understanding the past.” said Thompson. For more information: www.plos.org Image courtesy of Victor Thompson/University of Georgia]]>

Ancient Terraforming: Mound Key, A Calusa City Built on Shells