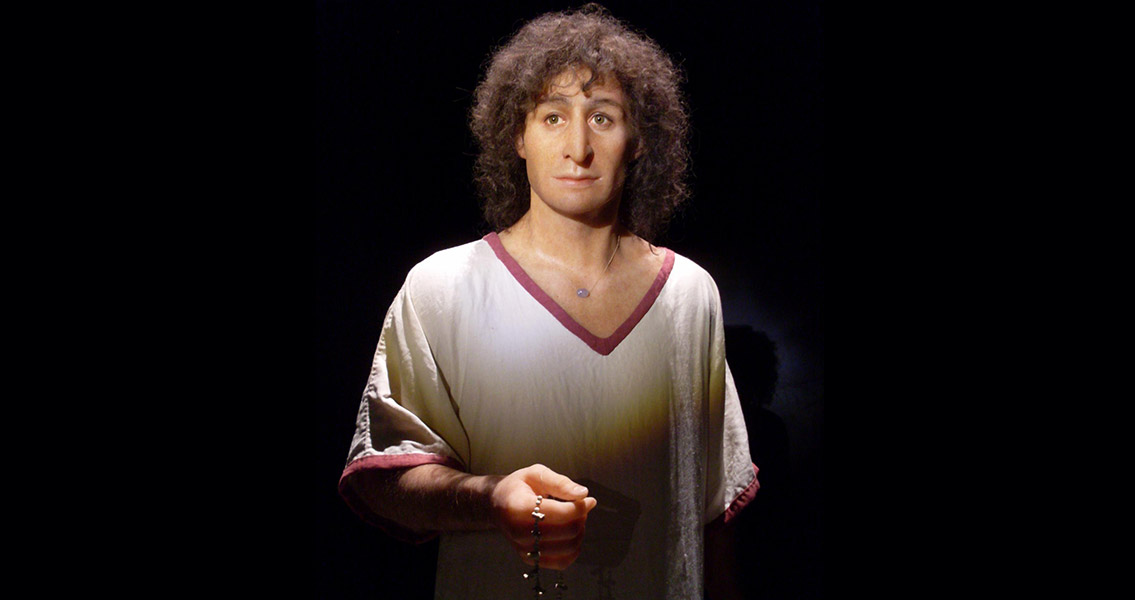

<![CDATA[The remains of a 2500-year-old Phoenician found in Carthage, after being exposed to mitochondrial genome sequencing, reveal the young man to belong to a rare European haplogroup. Researchers from the University of Otago in New Zealand completed the project, the first of its kind to be conducted with Phoenician remains. The young man, nicknamed “Ariche” or “the Young Man of Byrsa”, belongs to the haplogroup U5b2c1; the presence of the haplogroup has now been traced to the sixth century BCE in regards to when it reached North Africa. The haplogroup, which is a genetic group with a common ancestor, links the maternal ancestry of the young man to individuals that inhabited the North Mediterranean coast. The likely geographic location is the Iberian Peninsula, the site of modern-day Spain and Portugal. In a press release from the university’s Department of Anatomy, Professor Lisa Matisoo-Smith, the co-leader of the study, says that U5b2c1 is thought to be one of the oldest European haplogroups currently known, and has an association with hunger-gatherer populations in Europe. The genetic lineage is incredibly rare in modern populations, as it is only present in less than one percent of the population in modern Europe. However, the researcher revealed that the mitochondrial genetic make-up of Ariche was actually a close match to a genetic sequence source from someone living in modern-day Portugal. Phoenicians founded Carthage in North Africa, in modern-day Tunisia, as a major port city to help establish and maintain Punic trade routes with the center of their civilization in the Levant, what is now Lebanon (on the Mediterranean coast north of Israel and west of Syria). With the region being the cradle of the Punic civilization, the team sampled the mitochondrial DNA of nearly 50 modern Lebanese individuals but found no evidence of the European U5b2c1 genetic lineage. The European haplogroup was likely displaced by farmers that migrated from the Near East, Matisoo-Smith remarked, but based on previous research that discovered U5b2c1 in ancient hunter-gatherer remains found in the northwestern reaches of Spain, she said that this lineage might have survived long enough in the hinterlands of the Iberian Peninsula and islands off the shore to eventually be transported to North Africa through Punic trade routes, especially since Carthage was such a crucial port for the Phoenicians. The influence of Punic trade and cultural exchange cannot be understated, as the professor pointed out; the Phoenicians introduced the first alphabetic writing system to Western civilization. Despite this, there is still not much known about the Phoenicians themselves. Matisoo-Smith noted that most of the accounts that do exist – remnants from Ancient Greek and Roman sources, two civilizations that were in direct competition with the Phoenicians and thus heavily biased against them – are of questionable merit when it comes to presenting the Phoenicians in a truthful light. She hopes her team’s findings, and other research into the civilization and its culture, will yield fruit. The research study is available online from PLOS ONE Image courtesy of M.Rais]]>

Ancient Phoenician Found in Carthage Had European DNA