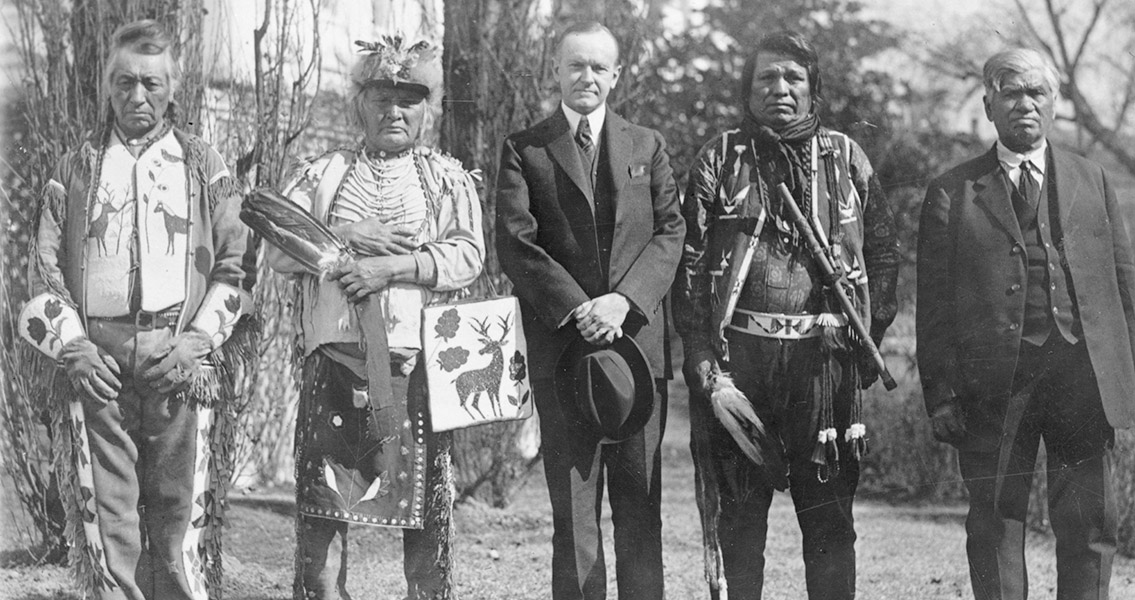

<![CDATA[2nd June marks the anniversary of the Indian Citizenship Act passing into law in 1924. A significant step in the Native American Civil Rights Movement, it nevertheless revealed just how much further the Native American people had to go in their pursuit of fair treatment. Also referred to as the Snyder Act, in reference to the bill's sponsor, Representative Homer P. Snyder of New York; the Indian Citizenship Act conferred citizenship on all Native Americans born within the territorial limits of the United States. “Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That all noncitizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States: Provided, That the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.” President Calvin Coolidge, who had signed the Act, spent much of his presidency trying to appear as a supporter of Native American rights. As the Act was publicly announced, Coolidge posed for a photo with three Osage Indians, two of which were wearing traditional ceremonial dress, outside the White House. Prior to the passing of the Act into law, the USA did not recognise Native Americans as US citizens; excluding them from the rights and guarantees given in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Until 1924, citizenship had only been available to those of 50% or less Native American heritage, or Native American women who had married US citizens. The 1887 Dawes Act had been the previous benchmark of US policy towards Native Americans. It dissolved all Native American tribes as legal entities and redistributed land among individual heads of family, who would become federal and state tax payers. Any remaining land was then deemed surplus and sold off, with the proceeds going towards building Native American schools. Masquerading as a reform to benefit the indigenous people, the Dawes Act’s impact was often the opposite. By 1932, the sale of unclaimed land under the Dawes Act had seen total Native American territories in the USA fall by two thirds. Meanwhile, it left the Native American families with an impossible decision: assimilate into white American culture, or preserve their heritage in poverty. It was a dilemma the Indian Citizenship Act failed to alleviate. Voting rights were not even guaranteed to all Native Americans by the Indian Citizenship Act, denying them the opportunity to meaningfully participate in the US democracy. The US Constitution allowed the states to determine their own voting laws, which meant they could place education or property ownership obligations on their electors to exclude the majority of Native Americans. It wasn’t until 1957 that all states allowed Native Americans to vote, highlighting just how arduous the battle for Native American Civil Rights has been. As has often been the case in US history, the Indian Citizenship Act laid the grounds for Native American assimilation into US life through citizenship, at least showing a difference in perception towards Native Americans. It provided little opportunity however, for Native Americans to defend their dying heritage or achieve true equality and freedom in US society.]]>

Anniversary of the Indian Citizenship Act Passing into Law