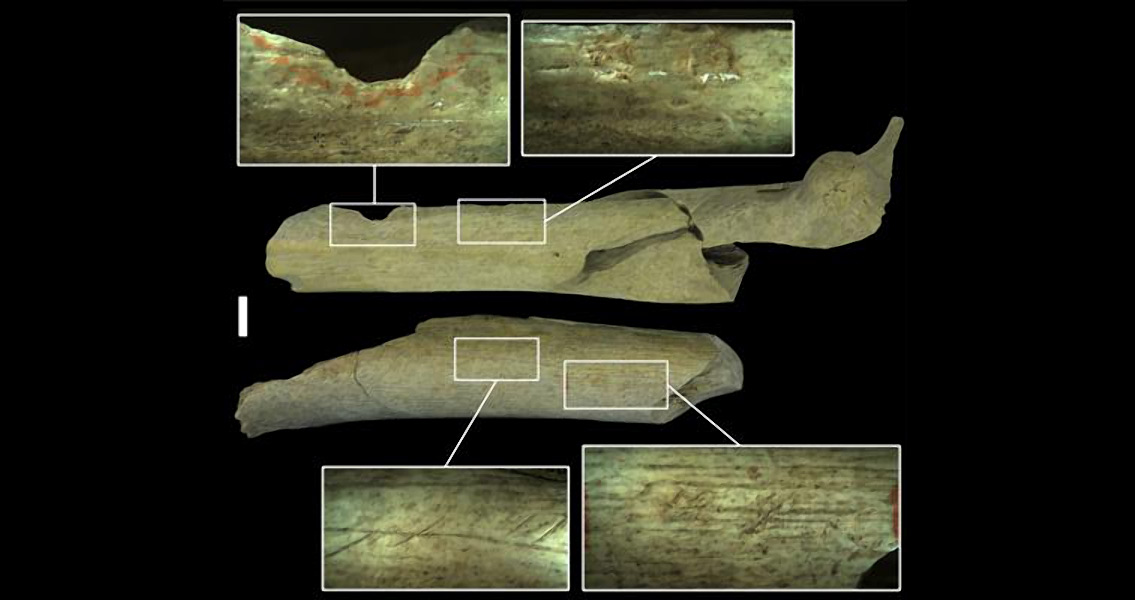

<![CDATA[The first evidence of Neanderthal cannibalism in northern Europe has been discovered at a cave in Goyet, Belgium. The four adults and one child unearthed at the Troisième caverne constitute the biggest haul not only in terms of the amount of remains found but also the number of individuals represented in a site north of latitude 50º. Signs of Neanderthal cannibalism are present on some of the 99 skeletal remains, as well as evidence that bones were used as percussive instruments to help shape soft stone tools. Led by Dr Hélène Rougier, the new study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, has helped expand the knowledge of known Neanderthal behavior in relation to the dead in northern Europe. As more and more insights are gradually revealed about the behavior of the Neanderthals, humanity’s closest extinct relatives, it becomes apparent that they displayed significant variability in their actions and customs. This perhaps shouldn’t be surprising, that different groups of Neanderthals had different practices, just as is the case among different groups of humans. This diversity of practices is clearest in the ways the Neanderthals dealt with their dead. At some sites, there is evidence that they buried the deceased. At others, there is evidence of cannibalism, that they broke the bones and ate the meat of other Neanderthals for food. These cannibalistic practices have been discovered at sites in both France and on the Iberian Peninsula. Neanderthals lived between roughly 200,000 and 30,000 years ago in Eurasia. Their appearance was similar to modern humans, though they were shorter, stockier, and had angled cheek bones, prominent brows and wide noses. Evidence has been found that they used tools, controlled fire, and in some cases (Chapelle-aux-Saints in France, and Sima de las Palomas on the Iberian Peninsula for example) buried their dead. Until the latest study however, the paucity of remains discovered north of latitude 50º meant it had been difficult to gain insight into how Neanderthals in the northern latitudes treated their dead. A third of the Neanderthal remains discovered at the Troisième caverne had cut marks, and a plethora had been crushed to extract marrow. The Neanderthal remains had been treated in a similar manner to horse and reindeer bones at the site, suggesting that all three species had been prepared and consumed in similar ways. Other Neanderthal remains at the site showed signs of having been used as soft percussors to shape stone. It is the fourth time a site has been found with evidence Neanderthals used the bones of their deceased to shape stone tools, joining Krapina in Croatia, and Les Pradelles and La Quina in France. Whereas the previous sites only contained a few examples of bones being used on tools, five sets of remains at Goyet had been used as retouchers. Due to their remarkable state of preservation it has been possible to date the remains at Goyet to between 40,500 and 45,500 years old. It has also been possible to extract the mitochondrial DNA of the remains, revealing that the Neanderthals at the cave were most similar genetically to those found in Feldhofer (Germany), Vindija (Croatia) and El Sidrón (Asturias, Spain). Such genetic similarity over such large distances suggests that the Neanderthal population of Europe was quite small. Earlier studies of partial Neanderthal skeletons discovered at Feldhofer, Germany and Spy, Belgium, showed evidence that Neanderthals had interred their dead. This latest study only adds to the increasingly complicated image of the contrasts between the different groups of humanity’s extinct cousins. Image courtesy of Asier Gómez-Olivencia et al.]]>

New Evidence of Neanderthal Cannibalism Found in Belgium