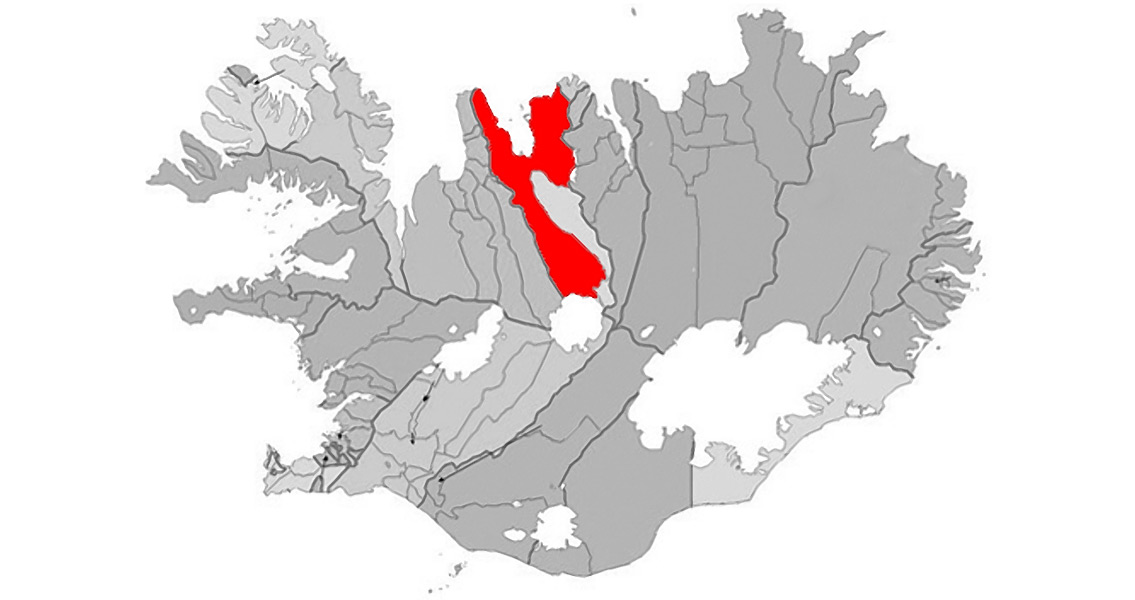

<![CDATA[In northwest Iceland, there’s a region where horses outnumber people, where archaeologists have been working for the past 20 years: Skagafjörður. Recent excavations there have focused around the city of Keflavík, where findings include a relatively large church with an adjacent circular churchyard, including approximately 45 graves. The churchyard/graveyard was used from the year 1000 CE (when Iceland converted to Christianity), until after 1104 CE, when the Hekla volcano erupted, blanketing the country with ash. This volcanic event allows the researchers to date their findings, like the numerous skeletons which were recently recovered from the churchyard graves, with a level of certainty. Skagafjörður is one of the most flourishing agricultural regions in Iceland, with extensive sheep and dairy farming, as well as horse breeding. It’s also had a significant role in the history of Iceland’s settlement. Skagafjörður was home to numerous historical events that influenced Iceland’s social and political development, and has a variety of valuable sites related to Icelandic history. It’s said that just below any surface within the valleys and fjords of Skagafjörður and northern Iceland, the remains of the structures built by the earliest settlers can be found. One of the most famous sites is Glaumbær, in Skagafjörður. Now a museum, it was once the home of the mother of the first European to be born on the American continent. In addition to the church and graveyard, two unique items have also been discovered: a bone pin adorned with an animal head, and a silver coin. The coin is slightly similar to others discovered in Nordic countries, but with distinguishing features. It will be sent to experts to be examined. Another bone pin was discovered at Keldudalur, a nearby site. The site at Keldudalur is a unique example, in many ways, of the composition of an Icelandic household in the eleventh century. Within a two-year span, an early Christian graveyard, a pagan cemetery, and the Viking-Age village associated with it, all came to light in the course of various construction activities. The Christian cemetery is the most complete eleventh century cemetery to be excavated in Iceland, and the well-preserved skeletons have been valuable resources. Keldudalur is an important resource for information pertaining to local and regional development during Iceland’s earliest history, for which written records are lacking. The habitation of Iceland is traditionally believed to have started in 874 CE, when Ingólfr Arnarson, a Norwegian chieftain, became the island’s first permanent settler. In the centuries that followed, Norwegians, and to a lesser extent other Scandinavians, settled in Iceland, bringing thralls of Gaelic origin with them. Ancient records indicate the Papar (Celtic monks), who may have been associated with a Hiberno-Scottish mission, settled in Iceland before the Scandinavians. Archaeological excavations have unearthed the ruins of a cabin on the Reykjanes peninsula, which carbon dating suggests was abandoned between 770 CE and 880 CE. Guðný Zoëga, with the Skagafjörður Heritage Museum, led the excavation at Keflavík. ]]>

One Church, One 1,000-year-old Coin, and Many Graves in Iceland