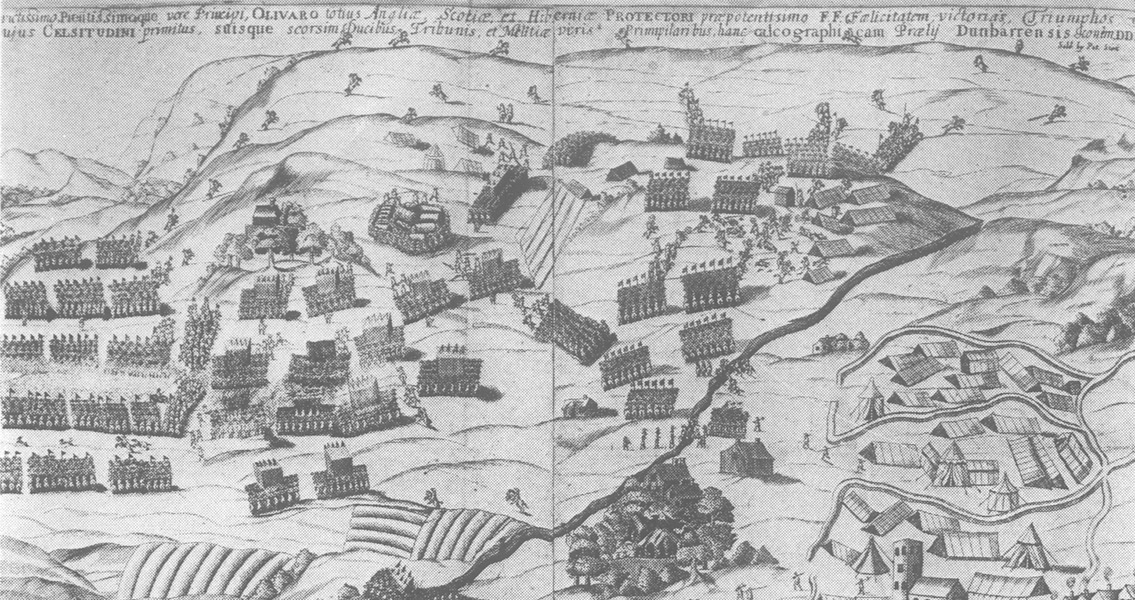

<![CDATA[Durham University recently announced that the skeletal remains of approximately 1,700 soldiers and prisoners of war from the Battle of Dunbar, which were discovered in a mass grave on the grounds of the university, will be reburied in the city. The decision follows a number of meetings and lengthy consultations where there were several calls for the remains to be returned to Scotland on moral grounds. Professor Chris Gerrard, who heads the Scottish Soldier Research Project at the university, explained the decision to Culture 24, stating that the fragile condition of the remains and the fact that they were separated and “incomplete” were important factors in the decision-making process. He’s quoted in Culture 24 as saying, “We felt that we should try to limit the distance, wherever possible, between the human remains that have already been moved and those which are still in situ. We are left with a situation in which different parts of the skeletons have been retrieved from the archaeological site and others are still left under the buildings on Palace Green”. Adding, “We feel that the human remains should be interred as close as possible to their comrades. These are men who fought together and died together. To separate them in death would be insensitive.” The Battle of Dunbar (September, 1650) was fought between English forces under Oliver Cromwell, and an army comprised of Scottish, Albanian, and French soldiers loyal to King Charles. It’s considered one of the bloodiest battles of the seventeenth-century English Civil War. Following the English army’s victory, approximately 5,000 soldiers were taken prisoner at Dunbar and forced to march over 100 miles towards England to the south, to prevent any rescue attempts. The conditions during the march were so appalling that many of the men (as many as 2,000) died of illness, starvation, or exhaustion, more than the total number killed during the battle itself. The prisoners were held at Durham Castle (recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986) and its empty abandoned cathedral, with many of the survivors later transported to New England, Virginia, and other places around the world to become indentured servants. Durham University’s Department of Archaeology, having retained a small sample of the remains, will continue their research and hope to discover new information about the health of the soldiers as well as their origins. A plaque in the Chapel of Nine Altars at the cathedral, which states the soldier’s burial place is unknown, will be corrected and then rededicated, and a commemorative plaque to be placed at the cemetery is currently under consideration. Professor Gerrard states in Culture 24, “Reburial in Durham is in accordance with English law and it reflects the standard approach set out by the Ministry of Justice license. It also conforms with best archaeological practice. It was clear from the consultation process that the public felt that there was a need to ensure these individuals were provided with a respectful and dignified burial. We feel comfortable that reburial in Durham, with an appropriate grave marker and a ceremony, offers these two things.” ]]>

Remains of Soldiers from the Battle of Dunbar will Remain Together