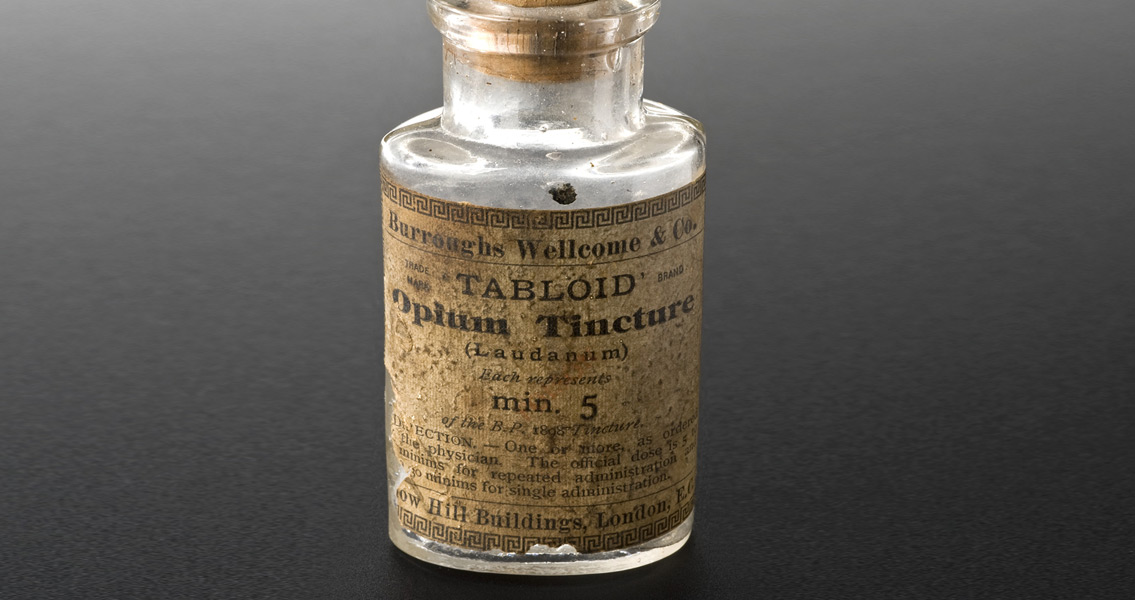

<![CDATA[It's difficult to imagine now, but from 1898 to 1910 heroin was marketed as a cough syrup and treatment for migraines. In 1886, John Pemberton included cocaine as the main ingredient of his new soft drink, Coca Cola. In 1910, the French were consuming over 36 million litres of absinthe a year, the potent alcoholic drink even used as treatment for soldiers suffering from Malaria. The period from 1870 to 1914 is referred to by some historians as the Great Binge. It was a time when stunning advances were made in pharmaceuticals and chemistry. Numerous drugs were developed, widely sold and consumed with little regulation or prohibition. During the Great Binge, substances that are now some of the most vilified could be found advertised in newspapers and magazines, at times even marketed for children. It's a bizarre fact which shows the drastic shifts that have occurred in our understanding of narcotics and intoxicating substances. Heroin's history provides perhaps the most potent example of the extremes of the Great Binge. The drug was produced unintentionally by Felix Hoffmann, a scientist at the Aktiengesellschaft Farbenfabriken (what is today the Bayer pharmaceuticals company) in Elberfeld, Germany, in an attempt to manufacture codeine - a less potent and less addictive form of morphine. Hoffmann's experiment instead produced a substance one and a half to two times more powerful than morphine. Bayer marketed the drug under the brand name heroin as a non-addictive morphine substitute and cough suppressant. They also believed it could serve as a painkiller which would break morphine addiction. Unfortunately, heroin in fact metabolises into morphine in the body, affecting the brain much faster due to its solubility. Far from beating morphine addiction, Bayer had created a substance that was more addictive and faster acting. Opium was also marketed for its medicinal use, treated as something of a miracle drug. Since the middle of the nineteenth century the recreational use of opium had increasingly been decried as damaging and anti-social. Its medicinal use however, remained hugely popular. It was put into syrups to be given to fussy babies, as well as asthma treatments and painkillers. Similarly, cocaine, first synthesised in 1885, was initially celebrated for its medical properties. Sigmund Freud advocated it as a treatment for depression and sexual impotence. Pemberton put it into his soft drink because of its energising properties. Increasingly, cocaine, like opium, was included in over the counter medication for a variety of common ailments. Even Thomas Edison promoted the 'miraculous' properties of elixirs containing cocaine. In the USA and Europe, opium, heroin and cocaine were all used as ingredients in elixirs into the twentieth century. With no restrictions on acquiring these drugs, they became an acceptable part of life for a host of people across different social classes. Slowly but surely, the effects of these intoxicants on society became increasingly apparent and critics came out to publicly condemn them. One of the most influential in the USA was Samuel Hopkins Adams, who published an expose entitled: "The Great American Fraud". The article highlighted the misleading deceptions often found in the advertising of certain medicines, and the potential harm they could do. "GULLIBLE America will spend this year some seventy-five millions of dollars in the purchase of patent medicines. In consideration of this sum it will swallow huge quantities of alcohol, an appalling amount of opiates and narcotics, a wide assortment of varied drugs ranging from powerful and dangerous heart depressants to insidious liver stimulants; and, in excess of all other ingredients, undiluted fraud." Adams' expose ultimately contributed to the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act in the USA, placing an obligation on manufacturers to accurately label products containing alcohol, cocaine, heroin and morphine. However, accurate information alone wasn’t enough to break society’s dependency. On a global scale, the rehabilitation from the Great Binge only truly started with the Hague International Opium Convention of`1912. Signed by 13 nations from across the globe, the treaty which went into effect in 1915, saw the signatories agree to work together on controlling the manufacture and distribution of drugs including opium, cocaine and heroin. In 1919, the terms of the convention were incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles, seeing them applied globally. Although not ending the sale of cocaine, heroin and opium, the Hague Convention of 1912 marked a turning point, the moment governments started to take action against the detrimental effects of large scale drug abuse. In the following decades, it proved the basis for national drug control legislation in many of the signatory nations, laying the foundations for the familiar drug laws we have now. ]]>

The Great Binge: Heroin, Cocaine and Opium Over the Counter