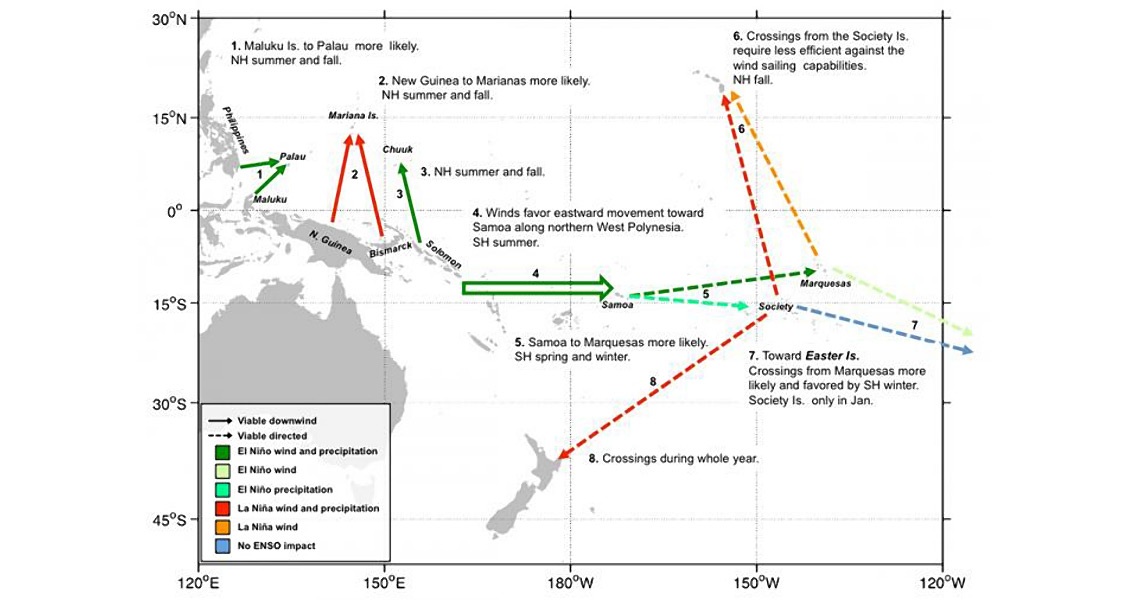

<![CDATA[The far flung islands of Oceania are among the remotest places on earth, yet somehow thousands of years ago seafarers managed to cross the great expanse of the Pacific Ocean and colonise the region. Taking place around 3,400 years ago, the colonisation of an area that includes present day Tonga, Samoa, Micronesia, Micronesia and Fiji was one of the most remarkable population dispersals in human history. Now, new research is providing fresh insight into how these ancient travelers crossed thousands of miles of Pacific Ocean. "Where did these people come from? How did they get to these really remote places, and what were the factors, culturally, technologically and politically that led to these population dispersals?" said one of the study's co-authors, Scott Fitzpatrick, an anthropologist at the University of Oregon. "These are really big questions for Pacific archaeology and other related disciplines." Fitzpatrick, along with his two co-authors: Ohio State University geographer Alvaro Montenegro and University of Calgary archaeologist Richard Callaghan, set about trying to solve some of these questions using computer simulations and climatic data to analyse ocean routes across the Pacific. Their study, entitled: "Using Seafaring Simulations and 'Shortest Hop' Trajectories to Model the Prehistoric Colonization of Remote Oceania", has just been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The simulations ran by Fitzpatrick et al took into account high resolution data for winds, land distribution, precipitation and ocean currents. “We synthesized a lot of new climatic data and ran a lot of new simulations that are exciting in terms of highlighting and pinpointing where some of these prehistoric populations might have come from,” said Fitzpatrick, in a press release. “The simulation can assess, at any point in time, if somebody left point A, where would they end up if they drifted? We can also model directed voyages. If somebody knew where they were going, how long would it take them to get there?” Interestingly, the team’s results suggest the settlers were aware of El Nino Southern Oscillation Patterns, and used them to aid their voyages. El Nino occurrences typically happen every three to seven years, and are shown in the archaeological record through evidence of forest fire and drought. One major consequence of El Nino is that winds and associated precipitation shift from westerly to easterly. Settlers would have found travel toward Oceania much easier during El Nino years, and could have timed their departures accordingly. “What Pacific scholars have long surmised but never really been able to establish very well is that, through time, Pacific Islanders should have developed a great deal of knowledge of different climactic variations, different oscillations of wind and changes in environments that would have influenced their survivability and their abilities to go to certain places,” Fitzpatrick explained. Information relating to the origins of the early seafarers has also been revealed by the study, occasionally challenging prevailing archaeological theories. The settlers of western Micronesia likely came from near the Maluku Islands, while those of East Polynesia probably came from Samoa. Hawaii and New Zealand on the other hand, may have been settled from the Marquesas or Society Islands. Easter Island was likely populated by people from Marquesas or Mangareva. The results suggest Samoa may have been an epicenter for colonisation missions, throwing into question existing data that have the Philippines as the possible point of departure for the colonisation of Micronesia. What the paper cannot answer is the tantalising question of why these early seafarers were driven to travel such huge distances. As the authors admit, there is no easy way to explain why people took the chance of launching colonising missions to islands up to 2,500 miles away. “What drove the movement? That’s the big question,” Fitzpatrick said. “Was it political? Was it a result of population pressure? There were probably multiple reasons why people decided to leave one place and go to another.” Image Courtesy of Scott Fitzpatrick ]]>

El Nino Likely Helped Ancient Seafarers Colonise Remote Oceania