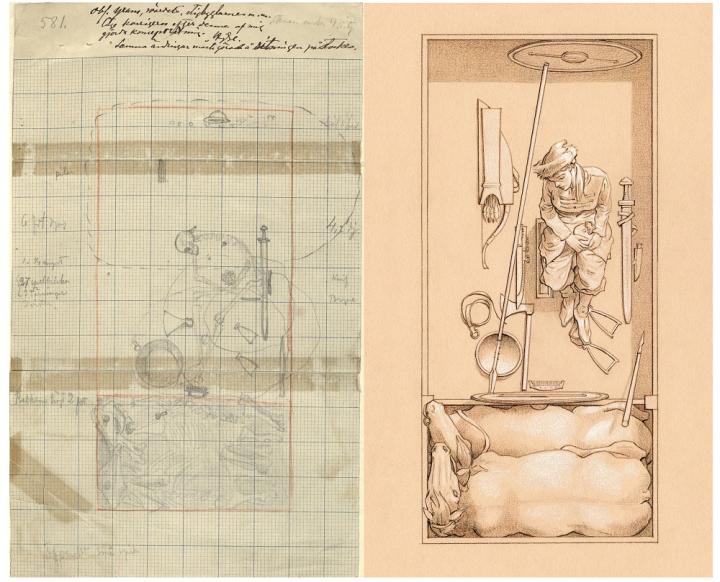

<![CDATA[The biggest history news stories of the last seven days, including two studies that could cause a rethink on the roles women played in our ancient history, and a remarkable find on the site of Hadrian’s Wall. Viking Woman was a Warrior and a Leader Viking society was not as male dominated as one might expect, a new study claims. According to new research from the universities of Stockholm and Uppsala, Viking women took on leadership roles on the battlefield. Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson, who led the study, explained: “What we have studied was not a Valkyrie from the sagas but a real life military leader, that happens to be a woman”. At the heart of the research, published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, is the grave of a woman Viking warrior, complete with the remains of two horses and a selection of weapons. Significantly, the burial also contained a set of gaming pieces and a gaming board among the remains. “The gaming set indicates that she was an officer,” said Hedenstierna-Jonson. “Someone who worked with tactics and strategy and could lead troops in battle”. Buried in the Viking town of Birka during the mid-tenth century, isotope analysis has shown that the woman had an itinerant lifestyle, commonplace in the martial society that was prevalent throughout Europe between the eighth and tenth centuries. First discovered in the 1880s, it was long assumed that the Viking warrior in the burial had been a man. Thanks to new research techniques however, that assumption has been comprehensively put to bed, allowing the remains to present a fascinating new dimension to Viking culture. Anna Kjellström, who also participated in the study, said: “The morphology of some skeletal traits strongly suggests that she was a woman, but this has been the type specimen for a Viking warrior for over a century, [which was] why we needed to confirm the sex in any way we could.” The team turned to genetics to confirm the Viking woman’s sex, retrieving a molecular sex identification based on X and Y chromosomes. “This burial was excavated in the 1880s and has served as a model of a professional Viking warrior ever since. Especially, the grave-goods cemented an interpretation for over a century,” said Jan Storå, lead author of the study. “The utilisation of new techniques, methods, but also renewed critical perspectives, again, shows the research potential and scientific value of our museum collections”. Women drove Bronze and Stone Age Cultural Exchange A new study has shown the importance of female social mobility for cultural exchange in Bronze Age Europe. Findings published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveal a fascinating trend among Bronze Age families in the Lechtal, south of Augsburg in what is now Germany. While the men in these families had tended to stay in the region of their birth, many of the women came from outside the area, possibly from Bohemia or Central Germany. According to the findings, the pattern of female mobility was not a short-term trend, but one that can be observed over an 800-year period during the transition from the Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age. “Individual mobility was a major feature characterising the lives of people in Central Europe even in the 3rd and early 2nd millennium,” stated Philipp Stockhammer from the Institute of Pre- and Protohistoric Archaeology and Archaeology of the Roman Provinces of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, the leader of the collaborative research project. The researchers suggest in their study that this mobility was significant in the exchange of ideas and objects, something which increased significantly in the Bronze Age and in its wake encouraged the development of new technologies. For this study, the researchers examined the remains of 84 individuals using genetic and isotope analyses in conjunction with archaeological evaluations. The individuals were buried between 2500 and 1650 BCE in cemeteries that belonged to separate homesteads, and that contained between one and several dozen burials made over a period of several generations. “We see a great diversity of different female lineages, which would occur if over time many women relocated to the Lech Valley from somewhere else,” remarked Alissa Mittnik from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, a contributor to the study. Corina Knipper, from the Curt-Engelhorn-Centre for Archaeometry explained: “Based on analysis of strontium isotope ratios in molars, which allows us to draw conclusions about the origin of people, we were able to ascertain that the majority of women did not originate from the region.” The burials of the women did not differ from that of the native population, suggesting that the formerly foreign women were integrated into the local community. As well as shedding new light on the role female mobility played in cultural exchange in the Bronze Age, the new findings point to the immense scale of human mobility in general in the period. “It appears that at least part of what was previously believed to be migration by groups is based on an institutionalised form of individual mobility,” concluded Stockhammer. Roman Barracks Unearthed Near Hadrian’s Wall Archaeologists have unearthed a 2,000-year-old Roman Barracks near Hadrian’s wall, the Guardian reports. Over the course of the last two weeks a “treasure trove” of thousands of artefacts has been unearthed, including military and personal possessions from Roman soldiers and their families, according to the Guardian. Remarkably, the barracks itself actually predates Hadrian’s Wall, allowing the findings to provide unique insight into the military build-up in the area prior to the Wall’s construction. Cavalry lances, arrowheads and ballista bolts are among the weapons found at the site, alongside combs, bath clogs, hairpins, brooches and stylus pens. The barracks, which date from 105CE, were discovered under the fourth century fort of Vindolanda, south of Hadrian’s near Hexham in Northumberland. According to the Guardian, the artefacts survived because they were concealed beneath a concrete floor laid by the Romans about 30 years after the barracks was abandoned, shortly before 120CE. The concrete created oxygen-free conditions that helped preserve materials such as wood, leather and textiles. Featured Image: Reconstruction of the Grave in Birka – The drawing is a reconstruction of how the grave with the woman originally may have looked. Credit:The illustration is made by Þórhallur Þráinsson (© Neil Price).]]>

History News of the Week – Viking Women, Cultural Exchange in the Bronze Age and a Discovery at Hadrian’s Wall