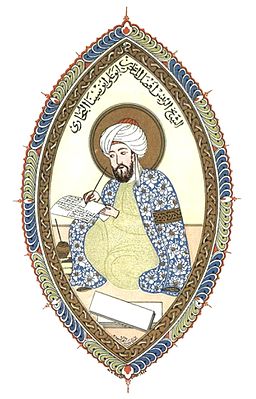

Origins Ibn Sina was born around 980 CE to a scholarly family near Bukhara (which was then in Iran and is now in Uzbekistan.) By the age of ten he had memorized the Quran. In the following years he continued to reflect on the Quran’s meaning and to study Islamic jurisprudence. He also studied logic and read the works of the Greek philosophers, mathematicians and metaphysicians, first under a tutor and then on his own. At the age of sixteen, Ibn Sina gave his attention to medicine—reading up on theory and also taking every opportunity for direct observation. Before turning twenty he undertook to treat the ailing Sultan of Bukhara, whose court physicians had failed to diagnose or treat his malady. Ibn Sina succeeded where the rest had failed. Unfortunately we don’t know what the diagnosis or the treatment were, only that the Sultan healed and, in his gratitude, opened the royal library to Ibn Sina, who was delighted to have access to many new works of science and philosophy.

Writings

Soon after this Ibn Sina himself began writing books setting forth the nature of the universe. This included broad theoretical explorations of philosophy, theology and metaphysics, observations on astronomy, mathematics, music and poetry, and practical advice on politics, household management, personal ethics, and medicine. His book “The Cure” seeks to draw the different branches of knowledge together and show them in their proper relation to each other, while many of his other works focus on specific branches of knowledge which had attracted his wide-ranging curiosity. Ibn Sina saw all knowledge as necessarily connected and made no sharp distinction between the academic and the practical. “Every science,” he observed, “has a theoretical and a practical side.” He added, “It is established in the sciences that no knowledge is acquired save through the study of its causes and beginnings, if it has had causes and beginnings; nor completed except by knowledge of its accidents and accompanying essentials.” This holistic view was particularly important in Ibn Sina’s theory and practice of medicine.Medicine

Today Ibn Sina is best known for his “Canon of Medicine,” a comprehensive guide to medical treatment. In this book he wrote about the ancient physicians—Chinese, Persian and Greek—whose works he had read, and about the fundamental similarities which undergirded their rather different approaches to medicine. He also realized that the classical authors hadn’t known all that was necessary, that medical knowledge still had a long way to go. So Ibn Sina included a detailed record of his own medical observations, and advised other physicians on how to record and evaluate their own observations.

He wrote about the importance of starting drug treatments at a low dosage and increasing the dose gradually; he also wrote about what type of consistent results were required in order to be sure of the effects of any particular drug. Michael McVaugh and other historians have described Ibn Sina as the first proponent of what we now call evidence-based medicine. He had a very optimistic view of what medical knowledge could eventually encompass: he wrote, “There are no incurable diseases, only lack of will; there are no useless herbs, only lack of knowledge.”

While Ibn Sina paid considerable attention to details of particular medical conditions (he may have been the first to recognize the distinctive sweet smell of the urine of diabetics), he also emphasized the importance of understanding the mental and physical health of the whole patient. He wrote, “Medicine is the science by which we learn the various states of the human body in health and when not in health, and the means by which health is likely to be lost and, when lost, is likely to be restored back to health….” He recognized that lack of health in one area of the patient’s life might show up in other areas—for instance, that apparent urinary tract problems might result from blood infections (a recognition which is said to have originated with him) or psychological disturbances. And he gave his attention to methods of preventing diseases as well as curing them, emphasizing diet and environmental factors. He studied how contagious diseases spread, not only though direct contact between people, but also through soil and water.

Today Ibn Sina is best known for his “Canon of Medicine,” a comprehensive guide to medical treatment. In this book he wrote about the ancient physicians—Chinese, Persian and Greek—whose works he had read, and about the fundamental similarities which undergirded their rather different approaches to medicine. He also realized that the classical authors hadn’t known all that was necessary, that medical knowledge still had a long way to go. So Ibn Sina included a detailed record of his own medical observations, and advised other physicians on how to record and evaluate their own observations.

He wrote about the importance of starting drug treatments at a low dosage and increasing the dose gradually; he also wrote about what type of consistent results were required in order to be sure of the effects of any particular drug. Michael McVaugh and other historians have described Ibn Sina as the first proponent of what we now call evidence-based medicine. He had a very optimistic view of what medical knowledge could eventually encompass: he wrote, “There are no incurable diseases, only lack of will; there are no useless herbs, only lack of knowledge.”

While Ibn Sina paid considerable attention to details of particular medical conditions (he may have been the first to recognize the distinctive sweet smell of the urine of diabetics), he also emphasized the importance of understanding the mental and physical health of the whole patient. He wrote, “Medicine is the science by which we learn the various states of the human body in health and when not in health, and the means by which health is likely to be lost and, when lost, is likely to be restored back to health….” He recognized that lack of health in one area of the patient’s life might show up in other areas—for instance, that apparent urinary tract problems might result from blood infections (a recognition which is said to have originated with him) or psychological disturbances. And he gave his attention to methods of preventing diseases as well as curing them, emphasizing diet and environmental factors. He studied how contagious diseases spread, not only though direct contact between people, but also through soil and water.