Reasons for Leaving Many of the Irish immigrants in the 1800s were no more eager to leave their land for the US than Coxe and his ilk were to receive them. But living conditions in Ireland had become untenable. This was the result of a process that started long before the infamous potato famine. In the late 1100s Norman-English soldiers arrived in Ireland to help one side in a civil war and stayed on uninvited. Soon after, England’s King Henry II sent further troops and laid claim to Ireland. Over the centuries that followed, Irish laws were changed and Irish lands confiscated. By the 1700s, only 14% of Irish land was owned by Irish people. A considerably larger portion was worked by Irish farm laborers who grew food for export, sometimes going hungry themselves. In the early 1800s, Anglo-Irish landlords found it more profitable to raise livestock than crops for export. Tenant farmers were evicted in order to make room for larger pastures. Some of the evictees found day labor at other jobs. Some managed to get small plots of land and grow enough potatoes to keep themselves alive. Others, unable to make a living in their native land, emigrated to America. In the mid-1840s the fungal disease called late blight swept the country, rotting the potato crop in the field. In 1845 forty per cent of the crop was lost. Families who had been barely getting by began to starve. By 1855 one million people had died of hunger and disease (as food continued to be exported from Ireland to England). Many more emigrated to the United States. As smallholders fled, their land was bought up and enclosed for pastureland; even after the blight subsided in the 1850s, the problem of dispossession remained.

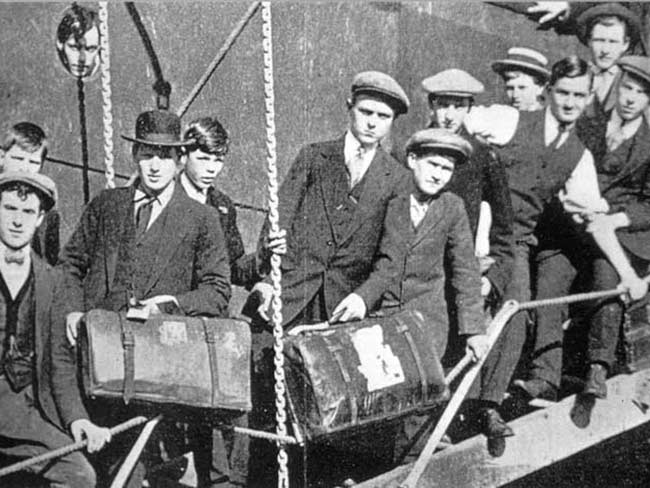

In the New World

The immigrants found work in the New World—often difficult work that offered little pay and less respect. Most of the women, who made up more than half of the exodus, became domestic servants or factory workers; most of the men found work building roads, railroads and canals or mining. Some US employers spoke quite frankly of hiring Irish laborers for jobs so dangerous that native-born workers wouldn’t take them. Some native-born workers complained that the Irish were impoverishing them by competing for jobs, driving down wages and taking charity. Certainly the landscape was changing fast. In the mid-1850s the majority of New York’s residents were immigrants, and the majority of recorded charity recipients were Irish. Some writers and speakers explained that this showed that the “Hibernian race” was naturally inferior to the Anglo-Saxon—conveniently overlooking the role played by Anglo-Saxons in displacing and impoverishing Irish emigrants. Irish immigrants were also the subject of wild conspiracy theories, often focused on their religion. Many writers alleged that the Catholics owed their true loyalty to the Pope rather than to any democratic government, and once sufficient numbers had arrived they would rise up violently, overthrow the Constitution, and subject Americans to a new Inquisition. Some went so far as to claim that a new Vatican would be founded in Ohio. In 1836 Maria Monk wrote what claimed to be a memoir about her life as a nun, in which priests were accused of lurid sexual misbehavior and routine child-murder; it was pointed out that she had actually never been a nun and the ‘memoir’ was actually a novel, but that didn’t hinder book sales. Sometimes anti-Catholic hostility led to apparently spontaneous rioting and violence, as in Philadelphia’s 1844 “Bible Riot,” over whether Catholic children should be allowed Catholic Bibles in school, left twenty people dead and three Catholic churches burned. In the 1850s anti-Catholicism found organized political expression in what was formally known as “The American Party.” The American Party appealed to “native Americans”—by which it meant US-born whites, not American Indians—to pledge “eternal hostility to foreign and Roman Catholic influence.” It sought to deport “foreign beggars and criminals,” bar Catholics from public office, and make immigrants wait 21 years for naturalization. This party successfully elected more than one hundred US Congressmen as well as gaining control of several state legislatures. The party began as a secret society whose members were instructed to answer any questions about outsiders with “I know nothing,” and the American Party was also known as the Know Nothing Party, the name by which they are mostly remembered today.

The American Party appealed to “native Americans”—by which it meant US-born whites, not American Indians—to pledge “eternal hostility to foreign and Roman Catholic influence.” It sought to deport “foreign beggars and criminals,” bar Catholics from public office, and make immigrants wait 21 years for naturalization. This party successfully elected more than one hundred US Congressmen as well as gaining control of several state legislatures. The party began as a secret society whose members were instructed to answer any questions about outsiders with “I know nothing,” and the American Party was also known as the Know Nothing Party, the name by which they are mostly remembered today.